My ride report from the 2016 Transcontinental Race is divided into two parts, with Days 7-13 below and Days 1-6 here. Please visit the Ride Far page dedicated to The Transcontinental Race or the official website if you’re looking for general information about the race instead of a personal race report.

Page Contents:

Part 2, Days 7-13

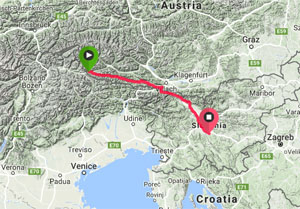

Day 7: Drava valley (Austria) – Ljubljana suburbs (Slovenia)

| Distance | 248 km |

| Climbing | 3540 m total (16m / km) |

| Moving speed | 23.2 km/h |

| Ride time | 14.5 hrs incl. stops, 11 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 9 hrs stopped, 5.5 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

My front tire had had a deformation since the start of the race, and the previous evening the fender had finally caused this to become a completely bald spot, so my first priority was finding a bike shop. Getting going early (before 6am) meant that despite there being bike shops in the valley that I was in, I needed one further along my route, and Google could only find a decent option about 95 km away.

The tubeless tire wasn’t able to hold any more air than it had the previous morning, so to make it last the 95 km, I installed a tire boot under the worn-out section and put an inner tube inside. The predicted rain started to fall as I climbed out of the valley, but the sky always looked clearer ahead so I kept pushing hard to stay away and was mostly successful.

The descent from the top of the pass at 1500 metres altitude to the next main valley at 700 metres was 40 km long, but was the most exhausting descent that I’ve ever done. Every time I lost a bit of altitude, the road kicked back up to regain at least half of what I’d descended. It was very twisty and the surface was poor, so it was not easy or fast. Fortunately, my legs were feeling fresh and normally I’d be loving such a quiet, twisty road in the mountains, so I tried to keep a positive attitude despite the route not being as efficient as I’d hoped.

Once into the next valley, I still had about 40 km left before the bike shop, and there was no guarantee that they’d have an appropriate tire because it appeared to be a very basic shop, so I was constantly nervous. My worries were increased when the front tire became very soft about 10 km before the shop. It must have been due to the inner tube being damaged under the bald section of tire, so I chose not to repair it and instead pumped up the tube every few kms and did several short sprints towards the shop between re-inflations.

The shop was called Bike PaRADies – RAD being short for fahrrad (bicycle in German) and paradies obviously means paradise. As I had suspected, it was a basic shop catering mostly to urban bikes and electric bikes, but they did have a couple of options of road tires, so I felt like I’d found paradise. I put on a new front tire and took a second tire to carry as a reserve plus some more spare inner tubes.

My brief ride through Austria was soon to end by taking the feared Wurzen Pass into Slovenia. The summit is only just over 1000 meters altitude, requiring just 500 metres of ascent, but that is nearly all done within 3 km. There is one 600 metre-long section that averages 19%, including one ramp of around 23%! Only a few TCR riders used this route, including the winner Kristof Allegaert, who told me during the finish party that he’d walked the steepest parts. Fortunately, my super-low gearing (34-tooth chainring and 40-tooth cassette) meant that I could pedal the whole way, but only just.

Approaching the climb, the storm clouds finally caught me and it started to rain very hard. The air was warm and I knew that I’d be working so hard up the climb that there was no chance of getting cold no matter how wet I got. I therefore got all of my important gear inside rain covers and put on my rain jacket without zipping it up and a baseball cap under my helmet to keep the rain out of my eyes, and left the rest of my raingear in my bags. I pushed on up the climb, and when I got to the steepest ramps I was only just keeping the bike moving forward. The people in the cars going past must have wondered why this crazy cyclist was choosing to keep riding in this horrendous downpour on one of the steepest climbs imaginable, and that is when I started shouting ‘ONLY IN THE TCR!’

In any normal situation, I would have chosen to wait out the storm somewhere sheltered, but as I had hoped, the rain eased once I reached the top. I wasn’t drying out quite as fast as I wanted to during the descent as the rain was still lightly falling, so I kept pedaling whenever possible to stay warm enough to be comfortable. Having full fenders/mudguards may have been part of the reason why my defective front tire failed, but I was now reaping the benefits of the fenders as I could ride on the wet roads without getting constantly doused with water coming off of the wheels, so I gradually dried out.

I always enjoy riding in Slovenia because it’s quite easy to find good-quality, quiet back roads and the scenery varies from being nice to fantastic. Plus, the drivers are typically courteous and supplies are easy to find at frequent petrol stations and grocery stores. I’d again chosen a route that optimized riding enjoyment over pure speed, and was loving it. By late afternoon, I made it to the capital city of Ljubljana. I wanted to briefly be a tourist and check out the central square and the famous Triple Bridge. On my way into the city, I found a McDonald’s where I picked up some fast calories to consume while sitting in the square next to the bridges.

I’d had a good sleep in a hotel the previous night, so planned to push on late into the evening and see how far I could get. My distance chart showed about 700 km to go until the town that marked the end of the Checkpoint 4 parcours/route in the Durmitor region of Montenegro or 650 km until the town at the start of it. I was therefore hopeful that I could make one of those in two more days plus the current evening.

About 5 km after leaving the city, more storm clouds started to approach. I pushed hard to avoid them but they came in too fast. The wind got to me before the rain and started pushing me along and I felt like I was surfing on the wind at the front of the storm and so kept pushing hard, often doing 40 km/h on the flat. The heavy rain then arrived and it quickly got dark so I didn’t see a pothole ahead that was filled with rainwater and rode straight through it, which caused my front tube to get a pinch-flat. I was relieved to spot a shopping mall nearby with a covered parking area that I dived into to fix it. I cursed the fact that if I had still been running tubeless tires, the pinch flat would have been avoided, but then the storm intensified and large hail stones started to fall and I decided that it was better to be comfortably under cover letting the storm pass than to have continued riding, and it didn’t really matter whether I had to fix a puncture or not.

Once the worst of the storm and hail had passed, the rain continued and evening was turning into night, so when I found a bar that offered rooms in the next town, I chose to stop and get an early start the next day to make up for the distance that I would lose that evening. While waiting for the waitress to organize a room for me, only costing 20 euros, I was entertained by a group of half-drunk middle-aged locals signing folk songs at full voice in a corner booth of the bar. It had been quite an eventful day!

Day 8: Ljubljana suburbs (Slovenia) – Croatia – Jajce (Bosnia-Herzegovina)

| Distance | 355 km |

| Climbing | 3690 m total (10m / km) |

| Moving speed | 23.5 km/h |

| Ride time | 18 hrs incl. stops, 15 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 7 hrs stopped, 5 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

The weather was thankfully dry when I got going early the next morning, but after less than 10 km I was surprised to find the road turn to dirt, and continue that way for almost 10 km more as it linked the top of one valley to the top of the next one. It was good quality, and I would normally enjoy such variety, but it was still a bit dark and the rain the previous evening had made the gravel soft and sticky, so it was hard work pedaling through it and I was happy when the tarmac started again and by then the sky was getting lighter.

After 90 km of rolling and hilly terrain, I reached the Croatian border and stopped for a second breakfast. I was crossing the narrowest part of Croatia where I was initially on a road with very few settlements due to the geology of the limestone region meaning that there is very little surface water and it is pockmarked with sink-holes. Where there were houses, they each had one or two small vegetable gardens at the base of sink-holes, but the rest of the farming seemed to have stopped. The road was quiet, with almost no locals on it, the only traffic was German and Dutch tourists who were looking for a more direct shortcut to get back home, but I’m sure that this twisty road wasn’t saving them any time over the more major alternatives.

In the town of Slunj, I joined the main road for a while and found a grocery store, but struggled to find anything substantial that I wanted for lunch. I ended up buying a bag of chocolate chip cookies, an extra-large pot of blueberry yoghurt, some crisps, and a couple of drinks. It would mark the start of surviving off of a random selection of odd foods from petrol stations and local stores with unfamiliar options; a pattern that would continue most of the way to the finish.

By mid-afternoon I crossed the border into Bosnia near the large town of Bihac. I hoped to find some hot, fast food there, but didn’t spot anything that would be simple, so instead snacked on whatever I found in my bags. After Bihac, there were some long, empty valleys, with wide-open vistas and a road that sometimes looked like it went on forever, which reminded me of certain parts of North America. I had a bit of a tailwind and so it didn’t take long to cover the kms.

My light tailwind was in stark contrast to what most of the other riders experienced as they had taken a route that went along the Adriatic coast. They reported gusty side and headwinds that were so strong that they could barely ride, and even when they tried to walk in certain sections they could barely hold onto their bikes as the gusts got hold of them. I was only 50 km inland but had fairly mundane weather.

I hadn’t seen anyone else from the TCR since leaving the Passo Gaiu in Italy, which was 5 countries and over 48 hours ago and I was starting to feel slightly out of my comfort zone in a strange land. It would be a further 36 hours, when arriving at the start of the Checkpoint 4 parcours, before I would see another understanding face that I could talk to properly. I didn’t even know the word to say thank you to the gas station clerks, so I was in my own little bubble. Just before sunset, I passed through the town of Kljuc, which was a massive difference to the empty valleys that I had got used to because the place was full of people and energy on the Saturday evening, which improved my mood slightly.

Constantly heading southeast and getting later in the year meant that the amount of daylight was decreasing significantly each day, with the sunset getting 10 minutes earlier per day when riding this part of the route. If I was staying still at home at this time of year then such a shift in the sunset time would take one week to happen! There was no moonlight, so I was limited to seeing the patch of road that my headlight could illuminate and I missed a lot of what I’m sure was impressive scenery in this area. Fortunately, the next valley had towns and villages scattered all the way along, so there were often streetlights to give me a better idea of my closer surroundings. I knew there was a major town beside a lake ahead and I hoped that I would be able to get a hotel there.

The town was 350 km into the ride, which is why I hadn’t been sure if I would make it that far, and I also didn’t have a data plan for my phone for that region, which is why I hadn’t tried to book a room earlier in the day. The town was full of tourists when I arrived and it was late on Saturday evening, so I was pretty sure that none of the hotels would have a room. I asked at one of the nicer-looking places, and he said there was absolutely no chance, so I decided not to waste my time asking anywhere else and headed out of town looking for a place to setup my bivvy bag along the side of the river.

This is another mentally challenging part of the TCR – doing a massive, long day on the bike, with no idea where or when you might find the best chances to refuel or where you’ll find a place to sleep for the night. At the end of a long day of riding, that is not the type of uncertainty that you want, but you just have to be adaptable.

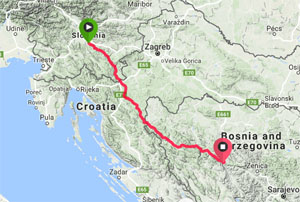

Day 9: Jajce (Bosnia-Herzegovina) – Drina valley (Bosnia-Herzegovina)

| Distance | 215 km |

| Climbing | 2250 m total (10m / km) |

| Moving speed | 23.0 km/h |

| Ride time | 13 hrs incl. stops, 9.5 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 7 hrs stopped, 5 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

For most of the previous day, the sky had a threatening look of impending rain. Luckily it never rained while I was riding, but it started just 5 minutes after I setup my bivvy. When my alarm went off well before sunrise, it was still raining outside, which gave me little motivation to get going, but I really wanted to get to the end of checkpoint 4 that day, which meant doing over 300 km. I lay there for a while and when the rain eased off briefly, I quickly took the opportunity to get out of the bivvy, dressed, and on the road.

I started the day in a tight river valley, then went over a decent climb which I pushed up hard to get the ensuing descent done before the rain re-started, which I was just able to do. I arrived in the next town as the rain starting falling again and so took the opportunity to refuel at a petrol station.

The rest of the day’s ride consisted of taking shelter during the heaviest rain and riding when it was lighter. By lunchtime, I had given up on my goal of reaching the end of checkpoint 4 by the end of that day. Not only was I running out of time, but the temperature had barely risen above 15 C all day so I was worried how cold it would be on the high passes in the Durmitor massif that we had to cross. My new goal was to reach the Drina river valley, about 70 km after Sarajevo. I knew that there was a town called Foca just off of my route where I could find a hotel because my friend Alain had stayed there during last year’s TCR. I would like to have continued onto Pluzine in Montenegro, the start of the CP4 parcours, but I wasn’t sure if there was accommodation there and I didn’t want to spend another night outside in the bivvy bag in the wet, so needed to be sure about getting a hotel.

As I headed towards and around Sarajevo, the roads became busier, but the traffic was never a big problem, which was a relief because I’d read some negative reports from racers who had ridden through in the previous year’s race. However, they had come in from the north and needed to go quite close to the center, whereas I was coming from the west and stayed along the southern edge, so it was generally OK, particularly because it was Sunday afternoon.

The road gently rose out of Sarajevo and eventually reached 1100 meters altitude. It was still drizzling, it was about 8 C, and there was some fog. I put all of my clothes on for the descent and turned on all the lights. Fortunately, the descent was mostly clear of fog and it was about 35 km of downhill through a fantastic gorge.

I was at a very low point mentally and was thinking about how nice it would be to have my wife waiting at the bottom to give me a big hug, but I jut had to keep battling the conditions on my own.

When I got down to the river I found a sign for a hotel just 1 km off of my route, which was even closer than Foca so I headed for it. It was only 6:30pm, but I had no more motivation to keep riding in the wet weather. The only room that the hotel had left was a cabin down by the river; the lady was very apologetic that it was a 3-person cabin and I would have to pay for all 3 people, and she was expecting me to walk away when she told me that the price was 30 euros, but I probably would have paid double that to not ride any further that day and I happily agreed. The cabin was great because there was loads of space to lay out and dry all of my wet gear, including the bivvy bag.

Stopping early meant that I had time for my first sit-down meal since leaving Switzerland 4 days earlier. Because it was called the Hotel Bavaria, the meal wasn’t so local, but was very filling and satisfying. I was able to treat myself to one local product – my only beer of the race :).

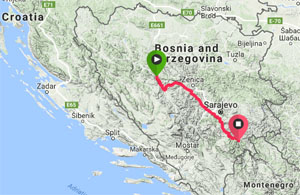

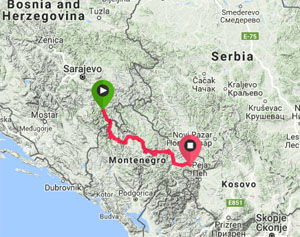

Day 10: Drina valley (Bosnia-Herzegovina) – Rojave (Montenegro)

| Distance | 246 km |

| Climbing | 3840 m total (14m / km) |

| Moving speed | 21.2 km/h |

| Ride time | 15 hrs incl. stops, 11.5 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 11 hrs stopped, 5.5 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

If I can pinpoint a section of my race where I could have done something different to reach somewhere sooner then it would be the ride between Checkpoints 3 and 4 on Days 7, 8, and 9. I was delayed during this section with (possibly avoidable) tire problems at first and later sought shelter from several storms instead of continuing to ride. However, I have absolutely no regrets about any of that now because getting to Checkpoint 4 any earlier would have meant that it would have been difficult to enjoy what was the most amazing section of riding of the entire race for me.

Other people’s favorite memories of the race may have been in France, the Swiss Alps, or the Italian Dolomites, all of which I enjoyed, but none of that was particularly new or special for me. In contrast, riding through the Drina gorge and the Durmitor national park in Montenegro was absolutely incredible and is something that I will remember for a long time. I’m so happy that I wasn’t there 12 or 24 hours earlier, because I’ve seen footage of people who were there then, and none of them looked like they were enjoying it very much in the cold and rain. As I said during this official TCR video below: ‘this was the right day, the right morning to come up here’.

Official video from Checkpoint 4, including brief appearance by me starting at 3:16.

I again left my hotel well before sunrise and then rode 20 km up the Drina river to the Montenegrin border. The road was pretty rough, but I enjoyed the challenge of weaving across the road from one bit of tarmac to the next to maintain speed as the road frequently undulated. After the border, the gorge became narrower and the morning clouds that were hanging around made the place feel like a set from a fantasy film. The road climbed up to the dam at the foot of the lake, and then went in and out of tunnels along the shore. There was a distinct line where the clouds finally stopped and I was into the full sun for the first time since Italy, which made my mood lift even further.

A long bridge took me across the lake to the town of Pluzine where the Zvono guesthouse marked the start of the official parcours for Checkpoint 4. I hadn’t seen any Transcontinental racers or organizers since Checkpoint 3 on the Passo Gaiu, so it was great to chat briefly with Anna and a couple of riders, but I wanted to press on into the Durmitor massif, so soon went back across the bridge. This time I took the road that climbed steeply away from the lake, passing through many more small tunnels as it zig-zagged up the cliffs.

During the climb, Bjorn Lenhard caught me. I’d met him before the start in Belgium and it was great to ride along exchanging stories. He’d been in second place through the Alps, but had a serious digestion problem and so stopped in Cortina for 36 hours where he planned to quit, but then things improved and he was able to continue, but he was now taking it relatively easy.

The high plateau at around 1500 metres altitude was amazing, dotted with small farms that had incredible views of the rocky peaks and deep gorges all around. As we were trying to take it all in, Anna and Francis came by in one of the official Volvo race vehicles and did some filming with both Bjorn and myself. After another short section of climbing, the road descended into a bowl and I spotted a park bench where I knew that I had to stop for a while to enjoy this awesome place. Soon Anna and Francis found me again and did some more filming.

It was one of my final equipment decisions to not bring my action camera this year because it was just one more thing to think about and complicate my life, and I wanted to focus on racing instead. It was a shame that this meant that I wouldn’t have any video of my trip, but in the end things worked out great because Francis Cade did such an excellent job of documenting each of the checkpoints in his video reports, and I was lucky enough to be moving between the checkpoints at a similar rate, and so he filmed me multiple times. Watch the video below or see the complete set of official TCR No4 videos or a playlist of Francis Cade’s vlogs from the TCR.

Video log from Francis Cade, including extended section with me starting at 1:01.

The official control for CP4 was at the end of the parcours, in the town of Zabljak, which was on another high plateau on the other side of the Durmitor massif. I had met Emily Chappell, one of the favorites for the women’s race before the start at the pasta cafe and we had chatted for a while. I had noticed that she was indeed leading all of the women and that I’d been quite close behind her ever since entering Switzerland, so was pleased to finally catch her in Zabljak. She’d just ordered two pizzas because she hadn’t eaten properly for a couple of days, so we spent a while discussing the foods that we’d been surviving off throughout the Balkans and found out that we had a few things in common including carrying more food in our bags than almost all other racers because we were always worried about running out and getting hungry.

There were several other people at the control and the volunteers were busy watching the dots to see who was approaching next. When they mentioned that a guy called Karl Speed was halfway along the parcours then I knew it was time for me to leave. As I mentioned in my Day 4 report, Karl met Alain a few times last year and had some great stories to tell about that race. We’d met at the start and then ridden up the Grosse Scheidegg climb together at CP2. Despite him taking a very different route south of the Alps to get to CP3 and then going along the Croatia coast while I went inland, we had remained closely matched. We’d joked with each other about who would reach the finish first, but neither of us was actually joking that much – we were actually quite serious and really wanted to beat each other. Stefan Slegl, a German rider, confirmed this when I was speaking to him at the finish; he told me that when he met Karl during the race then one of the first things that Karl said was that he had to catch this guy called Chris White. I was happy to leave CP4 a couple of hours before Karl would arrive, but at the time I wasn’t aware that from there we’d take almost the same route to the finish and that he’d stay hot on my tail.

After leaving Zabljak, I descended down into the upper part of the Drina gorge, the same river that I’d started the morning riding along. The upper part was almost as spectacular as what I’d seen earlier. Very few people live in that part of Montenegro, so my idyllic ride continued on an almost empty, incredibly scenic road for a further 70 km. I finally joined some busier roads for a while, but at the same time a tailwind picked up and I was flying along, so I was still loving it.

There was one more climb to finish the day where I had to gain 700 metres of altitude. Fortunately, it was quite gentle and I was still feeling strong, so I was even able to keep the chain on the big chainring for almost the first half of it. On the other side of the climb was the last town in Montenegro, Rozaje. I was tempted to continue and go over one more, even higher mountain pass and then do a long descent down into Kosovo before stopping that night, but I never like entering a brand new country at night when I don’t know what the roads will be like, the drivers, whether there will be a lot of wild dogs, how easy it will be to find a hotel, etc. I therefore went with the safe option and took the first hotel that I found when entering Rozaje, still in Montenegro. The guy at the check-in desk told me that a single room would be 12 euros and seemed to expect me to start haggling, but there was no way that I was going to do so over that price.

It was not only my second night in a row in a hotel bed but also my second night in a row eating in a proper restaurant. I was starting to get spoiled. However, I knew that this was all preparation for my sprint to the finish line because there was only about 930 km left so I didn’t plan to stop much more until I reached the end.

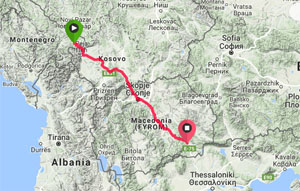

Day 11: Rojave (Montenegro) – Kosovo – Vardar valley (Macedonia)

| Distance | 337 km |

| Climbing | 2710 m total (9m / km) |

| Moving speed | 22.3 km/h |

| Ride time | 21 hrs incl. stops, 15 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 8 hrs stopped, 5 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

I wanted to get to Kosovo as early as possible, but first I had an hour-long climb and a big descent to do. With sunrise at 5:30am, I decided to get on the road at 4am to be at the summit at 5am, when it would be starting to get light to make the descent easier.

Shortly after starting the climb, I noticed a light approaching slowly from behind and soon discovered that it was Bjorn again. Chatting to him made the climb in the dark fly by.

I knew that Bjorn was a strong rider but I wasn’t aware at the time that he’d finished first in last year’s Paris-Brest-Paris race, a 1200km-long brevet ride with 5,000 people (but that’s another story). I tried to keep a decent pace, but a couple of times he told me that I should take it easier – he thought that it was too early to ride too hard. I was just happy that nearly all of my niggling pains and problems from the first week had pretty much completely disappeared and I was still able to ride strongly.

I started the day at 1000 metres altitude and the top of the pass is over 1700 metres, with the bottom of the descent at 500 metres, so I was prepared for a long descent but had no idea what the road would be like. The mostly gentle gradient of the climb meant that it had taken a little longer than expected so there was plenty of light. I normally descend faster than most people, but I soon learnt that Bjorn likes to descend even faster than me. Hurtling down the mountain at 80 km/h, heading into the unknown land of Kosovo, I again started saying to myself ‘Only in the TCR’, because there is no way that I would be passing between these countries on this road at this time of day in any other situation, or find someone else who is happy to be riding at 80 km/h down an unknown mountain pass before sunrise. Another special moment. I let Bjorn pass out of view ahead on the second half of the descent after we’d gone through the border post together.

I had several concerns about the road and traffic conditions on certain parts of my route through Kosovo and Macedonia. Mike Hall had stressed at the rider’s briefing that the minor penalties that were given the previous year to people using roads forbidden to cyclists would be far more severe this year. Avoiding such roads in western Europe is quite easy, but it is much trickier in SE Europe because as well as having a few proper motorways, many older roads have been upgraded to be major highways or pseudo-motorways. It’s then possible to find a section that is forbidden to cyclists when there is no alternative nearby, and such roads and restrictions are really difficult to research until you are actually there. Making a mistake may mean needing to do a lot of extra kms to find an allowable alternative or receiving a massive penalty, both of which I wanted to avoid.

I had therefore revised my route through Kosovo the previous evening to be more certain of avoiding any forbidden sections. This was an excellent decision because I found some really fun back-roads that showed me what life was like in the small towns instead of remaining on the big pseudo-highways. In one of the small towns, I even found a well-stocked supermarket where I could get some proper food that was much better than what I’d recently been surviving on from the highway gas stations. The store even had some bananas – my favorite fruit, which I hadn’t seen since leaving Slovenia. Kosovo seemed far more affluent and prosperous than most other countries in the region, and it was great to have a more complete impression of it than what I’d previously only seen on international news channels.

I’d been so pleased with the Kosovan back-roads that when I had to join the big highway leading to the border with Macedonia, I opted to take the one alternative road on the map. Unfortunately, this was a mistake because it turned out to be a really rough dirt road for more than 5 km and I got a pinch flat on the front wheel partway along.

After only 155 km in Kosovo, I entered Macedonia, where I had no choice but to go straight into the capital city of Skopje, which at half a million people was the biggest city of the entire race for me. During my route planning, I’d discovered a riverside bike path using Strava Heatmap that cut right through the city. It wasn’t the fastest option but was very calm and pleasant. There was just one small diversion away from the river right in the center of the city where I instead had to go through the central square, which was fortunate because it allowed me to see the statue of the local hero Alexander the Great.

To get from Skopje to Greece, I originally planned to take a major road southeast to the border with Bulgaria and then do a short section in Bulgaria before entering Greece, but then in Greece I may have to ride on a proper motorway for the first section. I changed my plan at the last minute to go slightly more south and not include Bulgaria, the advantage being that there was a new motorway along nearly all of this route and the old road still appeared to exist, so it should be a lot quieter than riding on the highway towards Bulgaria.

Unfortunately, my quiet ‘old main road’ wasn’t always what I had expected. Some sections were absolutely ideal. Other sections were terrible. The terrible parts included some really rough cobbles for a few kms, then a steep, twisty road up and over the hills that for a while didn’t look like it would continue all the way through, but thankfully it finally got me to the next town. This section had never been the main road – the main road followed the river but had been turned into the motorway.

Just before reaching Skopje, I had got my second rear puncture of the race. That tire was still tubeless, so I had inserted a plug/worm, pumped it back up, and hoped that it would reseal it like it had done on Day 3 in France. Unfortunately, the tire still kept deflating down to about 30 psi, so in the middle of one of the climbs, I gave up trying to repair it and decided to install an inner tube. While doing so, I switched the tubeless tire for the spare regular tire that I’d bought in Austria, because the regular tire would be easier to remove again if I got further punctures.

After the hilly section, my route was on the old main road that mostly followed the Vardar river, so I made good time. Unfortunately, my goal for the day of reaching the Greek border was still a long way off. I hadn’t eaten much all afternoon, and it was getting dark when I reached the town of Demir Kapija, so I was happy to spot a pizza restaurant / bar. It was a lively place where all of the young locals were hanging out and fortunately the waiter spoke enough English to understand that I wanted one pizza to eat now and one to take away with me (to get me through the big night ride that I was planning). I didn’t even try to discuss what kind of pizza I would get, and didn’t really care. However, during the ride I’d been fantasizing about having a big ham and mushroom pizza, so I was extremely impressed when the two pizzas that were delivered were both ham and mushroom. Score!

After the town, the Vardar river valley got very narrow and the motorway became a regular two-way highway, so I wasn’t sure if bikes were now allowed on it or not. I also knew that there was an alternative much smaller road on the other side of the river.

Just before entering town, I had got my third puncture of the day, this time from some debris on the side of the road that I went over when stopping to use the bathroom. While fixing it, a local cyclist came by who spoke good English and he had told me to take the small road for the next section, but he couldn’t understand why I didn’t want to stay in a hotel for the night and ride it the next morning.

It was dark by the time I’d finished my meal and I knew it would be 20 km through the valley before I got to any other settlements, but what I didn’t expect was that as soon as I left town, the road would turn to dirt. It was quite poor quality with some washboard sections, so I took it slowly in the dark, but hoped that the condition would improve, but instead it only got worse.

There were some short, steep ramps up and down, so I had to use some skill to maintain enough traction on my skinny tires. I was doing my best to be cautious and avoided most of the rocks and holes but after about 10 km I got a rear puncture due to the rim bottoming out and pinching the tube. By then, I was out of spare inner tubes, so I fixed the hole with a patch and glue without even removing the wheel from the bike. I couldn’t understand why the local cyclist had not mentioned the terrible quality of this road, but that’s probably why he thought it was best if I waited until morning.

I bring a pretty serious pump with me during the TCR because I know that under-inflated tires cost a lot of time in extra rolling resistance and greatly increase the risk of pinch flats. It has a small hose and a mini flip-out foot rest, so getting sufficient pressure isn’t a problem and it even has a pressure gauge, so I also re-checked that my front tire was well inflated despite it only being 12 hours since I’d last repaired a flat on that wheel. I rode even more cautiously than before, but got another rear pinch flat after a short distance.

I’m quite experienced at riding such roads on skinny tires and normally don’t have many problems, but I wasn’t doing a good job at avoiding all the obstacles in the dark despite having my powerful dynamo headlight plus an equally strong battery-powered light on my helmet. For some reason, I was just having no luck that day with punctures – this was my fifth flat tire of the day. Not getting frustrated took a lot of mental energy and I tried to calmly go about repairing another puncture as if it was my first of the day.

I’d started the race with tubeless tires specifically because they avoid nearly all pinch flats so riding on these kinds of roads isn’t so much of a problem. Due to issues with each tire, by 3000 km into the race neither tire was tubeless anymore. I’m no longer convinced that the extra hassle involved in setting up tubeless tires, the more restricted wheel/rim choices, and the increased difficulty in unmounting and mounting tight-fitting tubeless tires to install inner tubes is worth it when the tires may not remain tubeless for long enough to be there when you need them. Before this race, I was a big fan of using tubeless tires for races like the TCR, but now I’m far less convinced that they are the best option and wouldn’t bother using them again. Of course, other people used them without any problems (lucky bastards!).

It was now after midnight, but I wasn’t surprised to see another bike headlight coming down the track towards me. I once again thought ‘Only in the TCR’ – what other event could cause two cyclists to independently decide to ride down this wild dirt road in a remote part of Macedonia in the middle of the night and find each other? This race is truly special. We chatted briefly about the road condition and how we’d both been looking at the main road on the other side of the valley and wondering if it was legal for cyclists to use it and whether that would have been the better choice, but it was far too late now.

I decided to walk for a bit to avoid further punctures, but got bored of that quite quickly because even riding and fixing a flat every 5 kms wasn’t as slow as walking (although not by much), so I got back on the bike, but jogged down a few of the steep pitches. The end of the 20 km of dirt finally came into view, and just as I was celebrating being done with this nightmare, I got a front pinch flat! And then it started raining! Could this get any worse?

Where the dirt road joined the paved road, there was a railroad crossing and a small, abandoned signal-man’s hut. I decided that despite really wanting to do the final 40 km to the Greek border, it would be a much better idea to end the day here, get some sleep, and start again tomorrow with what would hopefully be a far better day with fewer problems.

I went into the hut out of the rain, ate some pizza and then fixed the puncture so that I didn’t have to deal with it in the morning. I lay in my sleeping bag for a while before going to sleep, thinking about what a long, crazy, event-filled day it had been.

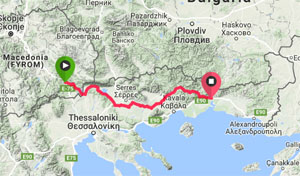

Day 12: Vardar valley (Macedonia) – near Xanthi (Greece)

| Distance | 319 km |

| Climbing | 2940 m total (9m / km) |

| Moving speed | 24.5 km/h |

| Ride time | 18 hrs incl. stops, 13 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 3.5 hrs stopped, 2.5 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

I woke up feeling surprisingly well-rested given that I’d only had 2.5 hours of sleep. It was still pitch-black outside, but the light rain that was falling earlier had soon stopped. I was looking forward to reaching Greece partly because my phone plan would again be valid there after not being since Croatia and I wanted to call my wife. I was also keen to check the race’s tracker website to see how far behind all of my delays had put me.

The border was on the south end of Lake Dojran and as I rode along the western lakeshore, the sun was rising over the Greek mountains, so I stopped briefly to enjoy the beauty of the moment.

Once on the Greek side of the lake, I stopped for a second breakfast of cold pizza and called my wife, who I hadn’t spoken to for a few days. Looking at the tracker, I’d maintained a similar overall position and my lead on Karl hadn’t really changed since leaving Checkpoint 4. Maybe everyone else had been having their own issues and delays.

The Greek highways made for fast riding and were virtually empty of traffic, but I had great memories from riding the TCR in 2014 of wonderful Greek back-roads, so I included as many of those as I could in my route this year and it really paid off. The next back-road went along the western shore of Lake Kerkini, which was very scenic and the region is popular with birds and so bird-watchers. I saw great numbers of various species, many of which I couldn’t recognize. It was a nice unexpected bonus aspect to my route choice.

By lunchtime it was getting seriously hot, up to 35 C air temperature, but the heat reflecting off of the road and the sun shining down from a steeper angle from above than I’m used to because of being further south made it feel even hotter. I stopped several times for cold drinks and ice creams and carried extra water that I could squirt directly into my helmet vents and onto my arms to keep my core temperature at a manageable level.

The obvious and direct route towards Turkey was to join the Greek coast in the city of Kavala, but that meant using part of the same route that I did in 2014 that wasn’t so interesting. I instead chose an ambitious alternative that stayed inland and went through the hills for 80 km before joining the obvious route in Xanthi. I stopped once more to restock my supplies before heading into the hills and at the same time checked my rear tire because it had been feeling a bit soft for a while, and indeed found that it had got another puncture.

This time, I couldn’t find the cause of the slow leak in the tube, so I was worried that something might still be embedded in the tire, ready to pierce the next tube that I put in. So to be safe, I put the tubeless tire back on, but still with an inner tube. It had been over 200 km since my previous puncture, so I was actually quite content because that was a far better rate than I’d had in the 200 km before that. I still had lots of patches and glue left so punctures weren’t going to stop me from getting to the finish. In the end, I thankfully didn’t get any more punctures in the final 400 km of the race.

My next equipment failure was my Garmin GPS device. It refused to charge, not with a wall socket, my battery pack, or dynamo hub, and not with any of three cables that I tried – the device’s charging socket was dead. I therefore resorted to backup navigation for the rest of the ride which was offline maps using the maps.me app on my iPhone with my planned route highlighted. I could leave the phone in airplane mode and asleep most of the time to conserve battery and then wake it up when I needed to check my position and to know which road I had planned to take. Fortunately, there were very few turns in the final 400 km of the route so it worked OK. I was also carrying a Garmin Edge 25 as a backup cycling computer, which is very small and simple and just gave me basic info like speed and distance and recorded everyting for Strava. Given how many other people had previously had their primary navigation device fail on them during the race, I had made sure that I was prepared for such an occurence.

Taking it easy all afternoon due to the heat and then having a break while changing the rear tire meant that I was well rested to tackle the hills. The sun was getting lower behind me and I felt strong so I attacked the climbs hard and whooshed down the descents for a couple of hours trying to stay ahead of the setting sun, which worked wonderfully. The road was absolutely awesome – almost no traffic, a perfect surface, great scenery, and twisty and undulating enough to keep it interesting but not enough to slow me down by much. This section is my favorite cycling memory of the entire race after the section through Montenegro that included the Durmitor massif. I knew that taking this route would cost me at least one hour compared to taking the shorter and easier coastal route, but I didn’t care because I was having so much fun.

There was a climb of over 300 metres towards the end of this section, when I did finally start to feel tired and the sun had properly set. From the top, it was another 20 km down to the town of Xanthi, but with a few more uphill sections along the way. Being that far south causes the light to disappear far more quickly after the sun sets and riding in the dim light was bothering me far more than normal so I was longing to be in Xanthi for the final 10km rather than still on that road, but the town eventually appeared.

I didn’t want to waste time at a restaurant, so instead found a small grocery store and bought everything that looked somewhat appetizing that I hoped would get me through most of the final 24 hours to the finish. I then sat on a park bench and had a feast of random foods. Problems with digestion are quite common in the TCR due to the odd diet, massive amount of calories, and physical exertion, but I am lucky in that my body seems happy to survive on whatever source of calories I give it.

It was now only 300 km to the finish and I knew that it would be at least as hot the next day, so it made sense to get as much riding done that night as possible. It was also the first night of the race in which there was any significant moonlight, which always makes night riding far more tolerable. However, the legs really didn’t have much energy after leaving Xanthi and my brain certainly needed some sleep, and the road was still quite busy, so I did one hour of easy pedaling before finding the edge of a field to setup my bivvy.

Alan Edgar had sent me a text message, so I had a brief exchange with him before going to sleep and it felt great to have contact with friends back home again. In 2014, he had got in touch when I was in the same region and I was going through a really tough time – I was going up a seemingly endless hill in intense afternoon heat. He had helped me get through that low point and now he had cheered me up before I went to sleep. Thanks Alan.

I was still worried about the position of Karl Speed. I knew that he’d done an extremely long non-stop push to the finish in 2015, so even though he was back in Kavala and I had a few hours lead on him and he appeared to have stopped for the night, I didn’t want to give him much of a chance to regain time. I therefore set my alarm to have about 3.5 hours of sleep, but was pleased to wake up after only 3.

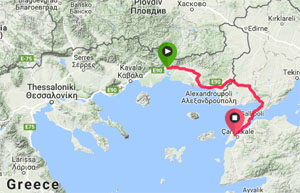

Day 13: near Xanthi (Greece) – Canakkale (Turkey)

| Distance | 277 km |

| Climbing | 2180 m total (8m / km) |

| Moving speed | 23.7 km/h |

| Ride time | 15.5 hrs incl. stops, 11.5 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 3.5 hrs stopped, 3 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

It was 3:30am when I got moving; my legs didn’t have much energy and my mind definitely wasn’t completely turned on that early in the morning, but I decided that it didn’t matter how fast I rode as long as I was on the bike and turning the pedals. Even doing 20 km/h on the flat would be OK; I only had 280 km left and I was just ticking off the kms.

I stopped in the park of the first large town to eat some breakfast and saw some drunk couples walking home after having a night out. My world felt so far away from theirs.

The legs started to wake up after breakfast, but the mind still wasn’t really there and I was longing for the sky to start getting light and the sun to rise. It was finally doing so by the time I reached Sapes where I had my only real dog chase of the race. I’d seen wild dogs frequently since entering Bosnia, but nearly all had shown no interest in me. For the few that did decide to start chasing my spinning legs, I’d used the tactic that Mike Hall had shown me, which was to roar at them as loudly as possible with a wild look in my eyes. It had worked 4 times out of 4 so far and the dogs had backed down immediately without me needing to sprint or confront them in any other way. Thanks, Mike!

Unfortunately, this dog was tougher than the others. He chased despite my roar, so I roared at him again, which seemed to make him keep his distance but he was still running with me and barking back. I continued with the roaring a few more times so he kept his distance until he decided that I had left his territory and gave up. I discovered that the one drawback of this method is that it may take a few days for your voice to get back to normal after an intense argument like this one.

I’d slept for less than 6 hours in the previous two nights, after averaging about 5 hours per night until then, so it was no surprise that I started to feel sleepy during a gentle descent shortly after sunrise. When my eyes weren’t focusing right, I started looking for somewhere to take a nap and soon found an inviting olive grove and fell asleep under one of the trees for 40 minutes.

After my refreshing nap, I only had to ride 15 km to get to the biggest town of the day, Alexandroupoli. I found a shop then sat on a park bench with a large coke and some snacks. I’d done over 90 km before 9:30 am, but it had seemed to take forever. I knew the finish was 180 km or so away, but in my mind that was an eternity because I had no energy in my legs and several body parts were now hurting in new ways. Until this point, I’d been doing pretty good physically, but it seemed that the body had shut down one day too early – or maybe I’d just paced it perfectly to collapse at the finish line.

The lack of physical strength was getting to me psychologically and this was by far the toughest section of the whole race for me to deal with, but I couldn’t quite understand why. I made a Facebook post about my struggles and almost immediately got back what I needed – a wave of support and well-wishes, including the comment below from Jeff Grant, who is a personal trainer and motivational speaker among many other talents (he’s also just written and published his first book):

‘Never easy, always worth it! Dig deep, my friend. These are the moments that make all the difference. These remaining 170km may be the longest of your life, yes…..so embrace that suffering and use it as fuel. Your ability to power through this is what you’ll remember 40 years from now. If you’re going through hell, keep going. Keep going, Chris. Keep going. We’re all behind you– feel that energy pushing at your back.’

Embrace the suffering and feel the energy pushing me is what I held in my mind and what kept me going for the rest of the morning. I got back on the bike and mentally celebrated every km that I passed and loudly rung my bell for every 10 km I completed.

I picked up the habit of using the bell to celebrate passing milestones from my wife Heather. Until the final day, I’d rung it when summiting a major climb and each time I’d passed 100 km. In fact, the first 100 km of the day warranted one ding, the second 100 km meant two dings, etc.; I was twice able to do four dings to celebrate reaching 400 km in one day, which felt really special. It was the final day, so a ding for every 10 km seemed appropriate. It was mostly down to Heather and Jeff that I got through this mentally-difficult section.

There was a variable cross/headwind that was getting stronger as I rode northeast towards the Turkish border, so I stayed on the aerobars, pushed on the pedals and thought about the messages of encouragement that people had sent me. Once into Turkey, the highway got bigger and there were energy-sapping rolling hills all the way to the town of Kesan, which marked the point at which I left my route from 2014 and started on a different road heading south towards the race’s new finish in Canakkale.

I arrived in Kesan around lunchtime so was very pleased to see that a Burger King had been built at the main intersection sometime since I was last there in 2014. I don’t know if the food was the best part, the air conditioning, or the proper toilets, but I definitely took my time over lunch. A guy came up to to ask if I was in the race and when I asked how he knew about it he said that he’d been hitchhiking around the Balkans and had met one of the media crews in Montenegro a few days before.

I checked the tracker and saw that there was nobody very close behind and nobody very close ahead, so I had no stress, it wouldn’t really matter exactly how fast I did the final 100 km to the finish. Looking at Karl Speed’s position, I couldn’t figure out what he was doing as he was off in the hills above Alexandroupoli where I wasn’t even sure that there were proper roads and he hadn’t been making much progress. When he reached the finish almost a day later, he had a long story about his adventure up there that involved running out of water and asking for some at a military camp, then having major bike problems, for which he had to go to Alexandroupoli to get fixed, and in the end he lost many, many hours due to trying to take a shortcut over the hills. However, it wouldn’t have been right if Karl had made it to the finish without having an incredible story to tell.

Video log from Francis Cade, including a very brief appearance by me at 3:35.

The wind was getting stronger in the afternoon, but I was turning more south so it was occasionally helping. The road had recently been turned into a major pseudo-motorway with heavy traffic, but fortunately there was a wide, good-quality hard shoulder for me to ride on. I was on my aerobars riding as efficiently as possible when a vehicle honked as it went past and I realized that it was Anna and Francis in the Volvo race vehicle. They were really apologetic when I saw them at the finish that they hadn’t stopped or at least slowed down, but seeing them was all that I needed to give me encouragement that the finish was getting close. Francis was even filming it and included the brief shot in his vlog abve.

My focus then turned to the final big challenge of the day, and of the race: a 300-metre high climb over a large ridge of hills, after which I would reach the Gulf of Saros and start the ride along the Gallipoli Peninsula. Like the previous afteroon, the temperature was again over 35 C, so my effort was not limited by my physical strength but more by my ability to manage my body temperature. I took it extremely easy up the climb so as not to overheat and it must have taken half an hour; I then stood up for much of the descent to allow the rushing air to cool me down as much as possible. I found a gas station at the bottom where I ate the most-needed ice cream of the whole trip.

I could see the highway going around the gulf and climbing up the ridge of the Gallipoli Peninsula for almost 20 km ahead. Every time I turned a slight right-hand corner the strong sidewind became slightly more of a tailwind, and I kept pushing on, knowing that it wouldn’t be far now and that there were no more major difficulties ahead and I was feeling stronger than I had all day.

Despite the size of the road and amount of traffic being like that of a motorway, there was no restricted access and other roads joined directly with no ramps or filtering lanes, so I had to remain vigilant. At one time an oncoming car was waiting to turn left across my lane and decided that a gap in the motorized vehicles was sufficient to make a dash for it, despite there being a cyclist approaching. If I hadn’t braked hard then I would have ridden into the side of him as he drove across the front of me, and my race would have been over just 50 km from the finish line. Phew!

I made a final stop at a gas station near Gelibolu with about 45 km to go. I knew the ferry times and saw that there was still no-one close behind me so decided that I could catch the ferry in 2.5 hours that would take me across the Dardenelles Straight to Asia and the finish line in Canakkale. Looking at my phone, I’d received several text messages from friends and family and also Facebook comments from people encouraging me to the finish line. I started to get emotional about the whole thing and got back on the bike with a lot of stuff to work through in my mind about what this all meant to me.

After leaving Gelibolu, the road got smaller and the traffic lighter, and the wind direction changed slightly to come more from behind and I was cruising along at over 30 km/h. I pushed it a little harder and easily reached 40 km/h. I started to wonder if I could make the ferry 1 hour earlier than planned and decided to push hard for 15 minutes and see what happened. I was able to average almost 40 km/h in that time so the earlier crossing became a serious possibility. I continued to push hard even when the road went up, and was spinning out my gears on the downhills. The road surface was generally great but a few patches were much rougher, but I kept the speed and went bumping over everything in my path, hoping that I wouldn’t get yet another puncture.

Having had very little energy for most of the day, I was now doing an all-out one-hour time-trial to finish the race. I had no idea where the energy had suddenly come from, but I was having a lot of fun.

With 20 minutes left until the earlier ferry, there was only 10 km remaining, so I knew that I’d make it. I then started to think about whether I might catch the one rider who had been some distance ahead of me. What if I came around the next corner and saw him just crusing along? How much of a shock would it be if I came by at full speed? Maybe we could have a sprint to the finish line for the coveted 28th place 😉

I kept riding as hard as I could until I reached the ferry terminal. As I frantically looked around for where to buy a ticket, a guy spotted me, realized that I was another of these crazy cyclists in this mad race that he’d seen several of before and so guided me over to the front of the queue. I then got on the boat with about 4 minutes to spare, extremely pleased with my effort for the final hour. I’d averaged over 37 km/h and looking at Strava now, I’m in the top 10 for the segment out of over 150 riders, many of whom were the other people during the TCR.

Once on the boat, I went in search of the other rider, a German guy called Benedikt Hartmann. I was still full of adrenaline, but he seemed a lot calmer and we spent the 30-minute crossing exchanging stories from the road. The finish line was only about 200 metres from the boat, and our positions had been set by the time of arrival at the ferry, so we cruised in to find several other racers waiting there and cheering us.

Due to the full-on final hour or so of the ride, there was no time to mentally process all of the stuff that I had expected to, and the finish was just an insane rush of adrenaline rather than an overwhelming outpouring of emotions. It certainly wasn’t what I was expecting.

My finish time of 12 days 20 hours and 36 minutes was well under my first goal of doing it in under 13 days. I did even better in regard to my second goal of a position in the top 20% – I was inside the top 30 out of 216 starters, or top 14%. There were a few things that didn’t go as smoothly as they could, but overall I had a great race, was enjoying myself for a lot of it, and achieved all of my goals in terms of seeing how much I am capable of achieving in this type of race.

Official video from the finish, including brief interview with me starting at 1:01, responding to the question ‘What have you learned about yourself during the race?’

Summary

Race Statistics

This map (click to enlarge it) shows my complete route, with the start, finish, and intermediate checkpoints marked in green and overnight stops marked in blue. More detailed maps for each day are shown with the daily descriptions, so click on the links above to see those.

I rode a total of 3,807 km (2366 miles) with 41,700 meters (137,000 ft) of climbing in 12 days and 20 hours. This makes an average of 297 km (185 miles) per 24 hours (range = 212 to 401 km) with 3,250 meters of climbing, so an average rate of climbing of 11 meters climbed per km (58 ft / mile).

There are many ways to spread 297 km of riding out during the day, so I kept some notes during the race and supplemented this with the data on my GPS to calculate the following statistics:

The mean elapsed time between the start and end of a day of riding for me was about 17 hours (range = 13 to 20 h). My morning start time varied between 3:00 am and 9:30 am (sunrise was typically around 6:00 am) and the time when I stopped in the evening varied between 6:15 pm and 2:00 am (sunset was typically around 8:00 or 9:00 pm).

I stayed in hotels on 6 nights and slept in a bivvy bag in quiet, rural, hidden locations the other 7 nights. During my average overnight stop of 7 hours, I slept for about 4.5 hours, but this varied between 2.5 and 7.5 hours on different nights.

During my average 17 hour day, I was on the bike and moving for about 13.25 hours (range = 9.5 to 17 h), giving an average moving percentage during the ride of 78% (range = 71 to 85%) and over the whole day I was moving 55% of the time. My average speed was 22.4 km/h (13.9 m/h) while moving and 12.4 km/h when including all stops.

I used a power meter and although I rarely looked at the numbers when riding (I prefer to base my effort on feeling during the race), it is useful to analyze the data afterwards. Interestingly, my average normalized power didn’t change much over the course of the race and varied between about 125 and 135 watts on different days. The total energy put into the pedals was about 60,000 kJ, which suggests an average daily caloric need of around 4,600 Calories for pedaling alone (I didn’t record my weight change or what food I consumed). Using a rough estimate of what my FTP probably was at that time gives a Training Stress Score (TSS) of about 200 per day, so 2,600 total.

[Note that some of these values don’t correspond perfectly with the values given for the daily descriptions above. That is because the values in this section are based on strict 24-hour periods (midnight-midnight) whereas some of the daily descriptions are divided differently.]

Lessons to Learn from the Numbers

I wasted a minimal amount of time during the day. I would have liked my moving percentage to have been above 80% during the day; I only achieved 78% but that was partly caused by my repeated tire and tube problems that I couldn’t control. The only way that I could significantly improve my moving percentage during the day would be to do more eating while riding instead of stopping to eat my main meals, but at the same time those stops were necessary for my body to have some occasional rest.

Averaging only 4.5 hours of sleep per night was not a problem for me, even though I normally average about 7 hours per night at home. Getting up in the mornings sometimes took a lot of will-power, but the only time that I felt tired while riding was on the final morning, so I then stopped for a short nap.

On the evenings when I stopped at a hotel, I did waste some time looking at social media and doing other non-essential tasks. Although this was not essential for making progress in the race, that time was important for me psychologically because I was taking time out to mentally relax and occasionally spend a bit of time not being in a hurry to do everything. It may therefore be unwise to completely minimize this aspect while still being able to enjoy and absorb the whole experience, but if I wanted to race more seriously then I could gain some time there.

I pride myself on making navigational errors extremely rarely, and that was again the case here. However, my route was not optimized purely for speed and was more of a balance between taking more interesting routes and enjoyable roads while still trying to make progress reasonably efficiently. Again, if I wanted to race more seriously then some improvements could be made to the efficiency of my routing.

I rate cycling speed as being less important in determining progress than is the amount of time spent off of the bike and how good the planned route is and your ability to follow it. Even so, cycling power and therefore speed is still important. Given my level of fitness entering the race, I don’t feel that I could have got much more out of myself in terms of pedaling power and I generally did a good job of staying well fueled, so I have no regrets there. However, if I wanted to race seriously then I would need to adopt a more rigorous approach to my training and do specific training rides and exercises to increase my capacity to maintain a higher level of power without causing any stress on my body; some off the bike work would also be helpful.

The final way to improve my performance might be to use different equipment. I certainly carry a bit more luggage than most other people in these races, but that is partly because I prefer to be prepared and not have to worry about unanticipated problems. In addition, I know from the results presented in the What Determines Cycling Speed? section that even a change in luggage weight of a couple of kilograms would not change my cycling speed by anywhere near as much as most people assume. I focus a lot more on the aerodynamics of my clothing than most other racers, which more than compensates for the marginal amount of extra weight that I carry, so I don’t wish to make any significant changes in my equipment choices (I mostly got that figured out during my first two races).

Results

As well as being more than satisfied with my personal performance, I was also pleased with my performance relative to the other participants. I came across the finish line in 31st place out of the 216 starters, which is in in the top 15%, so I was well inside my goal of being in the top 20% overall. 138 people (64%) finished the race.

My progress during the race was also satisfying because I started at a steady pace, reaching checkpoint 1 in 83rd place, but then moved up to 47th, 41st, 33rd at checkpoints 2, 3, and 4, respectively, before crossing the line in 31st. I had no particularly fast sections between any two checkpoints but apparently many other riders were slowing down during the race whilst I was able to better maintain my pace. Once penalties were added and people put into certain classifications, I was 25th out of the 84 solo, classified finishers.

This page is in the My Bikepacking Race Reports section. The next page in this section is: