Dogs are by far the most common problem in terms of animals that may attack cyclists but many other animals can cause a hazard by entering the road unexpectedly. Such problems are extremely rare in some regions, but are common in others. Ultra-distance cyclists are more likely to encounter animals than other cyclists due to covering greater distances and visiting more remote regions.

Page Contents:

Animals on the Road

This page mainly deals with incidents categorized as Type 3c on the Causes & Types of Bike Crashes page, “An animal attacks the cyclist.” Animals can also cause crashes of Type 3a, “An unexpected change in the road surface or other unexpected hazard appears”, by jumping out in front of the cyclist. There is not much that can be done to avoid those types of crashes except for staying alert (the potentially dangerous effects of Sleep Deprivation were covered on the previous page) and using good Headlights when riding at night.

Dog Attacks

Being chased by dogs is rarely a problem in northern and western Europe, but stray and wild dogs are quite common in certain parts of eastern and southern Europe. In North America, there are very few wild dogs, but it’s common in certain areas for domestic dogs to not have a leash and those often chase cyclists; many cyclists report that the region in the central Appalachian mountains is the worst. In Australia, dingoes can occasionally be a problem.

Compared to the number of dog chases that people report, the number of people who are actually bitten is extremely small, but bites do happen. If you are bitten, you should get a series of rabies vaccinations. It is also possible to have vaccinations before starting a race, which won’t make you immune but will reduce the number of vaccinations needed if you are bitten. See the American CDC website for more information.

You should have a plan for how to deal with dogs. Many dogs, particularly the wild ones in south-eastern Europe, tend to be more docile during the day and more aggressive at night, so the simplest tactic is to only ride during daylight, but some dogs will chase at any time of the day.

The most commonly used tactic is a combination of what I call the Pink Panther and Mark Cavendish techniques – once you spot a dog, enter stealth / Pink Panther mode and hope that the dog doesn’t see, hear, or smell you for as long as possible (unfortunately, the smell of many bikepackers gives away their presence quite quickly). Once the dog knows that you’re there and gives signs of chasing, many people then enter Mark Cavendish mode and do a full-on sprint. It’s amazing how much energy can be summoned in these efforts regardless of how exhausted and empty you were feeling 10 seconds beforehand, and often a 200-400 meter-long sprint is enough to stay away from the dog(s) and dissuade them from chasing further. Unfortunately, such efforts are less effective when going uphill and it is more common that people get injured by crashing their bikes while sprinting away from dogs than by being bitten by them; this is especially true during night-time chases when you may not see a pot-hole or other road hazard. Sprinting away from dogs is therefore quite a risky strategy.

A generally safer strategy for dealing with dogs is what I call the Mike Hall method (the founder of the TCR); he would look back at the animal and roar/scream at it violently with a slightly wild and crazy look in his eyes. When Mike demonstrated this to me at the finish party after the 2014 TCR, I decided that I would never be quite as good at this technique as he was – the look in his eyes was probably enough to scare away a grizzly bear. If you do this with some confidence then it can be very effective because most dogs are quite timid and quickly stop chasing. This strategy may be less effective when there are multiple dogs, as they then tend to be bolder and less intimidated. I used this technique in 2016 with multiple individual dogs, most of which immediately stopped chasing me, but one was bold enough to ignore my roaring, so I had to do a short sprint, but I was overall quite pleased with the technique.

To avoid losing your voice from all of the screaming, a small air horn can also be used and is generally quite effective.

Some people carry weapons to fight back at the dogs. Pepper spray is probably the most effective and humane technique, but is not legal in all countries (see responses to this post in the Trans Am Bike Race Facebook group). One rider in the 2015 TCR carried rocks in his jersey pockets to throw at the dogs, and managed to connect with one of his missiles on the dog’s head, which killed the dog. I’ve heard stories from two other TCR participants about dogs that were run over and killed by cars as the dog was in the process of chasing them.

Other people just stop their bike and get off. The dogs tend to only chase cyclists, so if you leave the bike and become a regular person, most dogs quickly lose interest. This is certainly a good tactic to use if you realize that the dog doesn’t back down by screaming at it, you cannot out-sprint it, and you have no horn or weapons. When getting off of the bike, try to keep the bike between you and the dog as a safety barrier.

A more devious method is the survival-of-the-fittest strategy. It involves riding with someone who is a slower sprinter than you are, then when the dogs start to chase, leave your partner behind to deal with the dogs while you head up the road. This is certainly not in the spirit of the camaraderie of the race.

Although dog chases will happen, they are nearly all quite benign and it shouldn’t be a great cause for concern or a reason to not enter a race. Most dogs are chasing either just for fun or as a territorial behavior, they are not really trying to hunt you even though it often feels like that.

Despite dogs being keen to chase moving cyclists, I’ve not read any reports of dogs attacking people while they were camping.

Bear Attacks

In the US, more people are killed due to allergic reactions from stings of bees, wasps and hornets than by any other animal (aol.com), so dangers need to be put into perspective. Bear chases are extremely rare, but they can occur and occasionally cyclists have been killed by bears. According to this article only about 150 fatal bear attacks have occurred since 1900 throughout all of North America, only a very small number of which involved cyclists. However, the video below is rather scary:

Most bear attacks are caused by cyclists startling a bear, crashing into one, or getting too close to a female’s cubs. So the best way to avoid attacks is by constantly making noise so the bears know that you’re coming and they’ll then normally stay away. If you’re on your own, you may choose to sing to yourself or if traveling in a group you can constantly talk to each other. It appears that although popular, bear bells are not actually very effective. Using bear spray is the best defense if you are attacked. You can read a lot more advice at BearSmart.com.

On very rare occasions, humans have been attacked by bears while camping. When camping in bear country, it’s therefore best to keep all food well away from the campsite and if possible do any cooking in a different location from where you camp.

Other Aggressive Animals

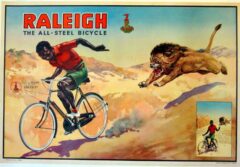

Dogs are the problem in over 99% of the incidents when cyclists are chased by animals. In certain regions, bears chases are possible but never common. There are also a myriad of other large animals that can on very rare occasions chase cyclists: There are some reports of wolves chasing cyclists in North America and lions do occasionally attack humans in Africa, but apparently one solution is to ride a really fast Raleigh bike (see the advertisement on the right). Even if you avoid the African lions, you may still need to look out for the ostriches, as shown in this video:

Last significant page update: December, 2017

This is the final page in the Rider Health & Safety section, which is in Ride Far, Part I: The Rider.