My ride report from the 2014 Transcontinental Race is divided into two parts, with Days 8-14 below and Days 1-7 here. Please visit the Ride Far page dedicated to The Transcontinental Race or the official website if you’re looking for general information about the race instead of a personal race report.

Page Contents:

Part 2, Days 8-14

Postscript from 2016: It’s interesting looking back at this report of my rookie edition of the race. I violated several rules of being self-supported in terms of equipment and information, mainly due to not being aware of what the rules/guidelines are. It wasn’t until the 2015 edition of the race that these rules were more clearly stated and emphasized. One of my goals for returning to the race in 2015 and 2016 was therefore to finish the race properly unsupported, which I finally managed to achieve in 2016.

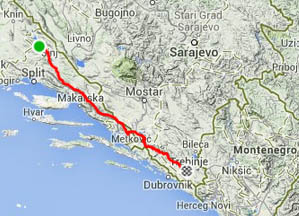

Day 8: near Rijeka (Croatia) – near Split (Croatia)

| Distance | 275 km |

| Climbing | 2560 m total (9m / km) |

| Moving speed | 23.3 km/h |

| Ride time | 16 hrs incl. stops, 11.5 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 11 hrs stopped, 7 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

The previous evening, I had met John, a fellow TCR rider, on the road to the Croatian coast, and we had shared a hotel room. In the morning, we took advantage of the hotel’s breakfast buffet, which started at 7am, so we didn’t get going too early. When checking the tracker the previous evening, we had seen that one more TCR racer had last been tracked in the parking lot of our hotel, and he showed up at our breakfast table shortly before we were ready to leave; a Swiss guy who lives near Zurich called Tim Arnold. We had a short chat before John and I hit the road.

We wanted to get to the town of Sinj that evening, 295 km away, because the other thing that we’d seen on the tracker was that all of the people that had taken the route down the Italian coast to Ancona to catch the boat across the Adriatic Sea to Split were quickly making up ground on us. Sinj is just inland from Split, so if we made it there then we’d be level with those getting off of the ferry the next morning.

The coastal road had several small climbs, swirling winds blowing from all directions, and a fair amount of holiday traffic. It was very scenic, but tough riding. We’d already planned to take the inland route instead of the coast road once we had the option, and our 30 km on the coast told us that this was a good plan. Before turning off, we found a good grocery store and I impressed John by how much my bags could expand to swallow a major supply of food and snacks for the next couple of days.

I was very pleased to find lip balm in the grocery store because my second physical problem (the first being a bit of nagging knee pain in the mornings) was that my lower lip had become quite damaged and swollen from being out in the sun, wind, and rain for the previous week. I hoped that applying the lip balm would protect it and help it to recover, but unfortunately this never really happened and it would continue to be a problem all of the way to Istanbul and would take almost two weeks to heal properly afterwards.

The climb to get away from the coast was a tough one – about 700 metres of ascent in 15 km, but we knew it would be worth it because the inland route would be flatter overall, quieter, and probably less windy. At the top of the climb, we awarded ourselves with an early (first) lunch.

The inland roads were better than we’d ever imagined – easy riding, with a gentle tailwind, and almost empty of traffic because there was a new motorway nearby that most of the vehicles were using. We were making good time, but then our road was blocked by some construction. The alternate road would add a fair amount of distance, so we checked out the closed road and saw that it was closed due to a bridge that was being repaired a couple hundred meters further on, which we could easily walk our bikes across. On the other side, we had the closed road entirely to ourselves for the next 20 km. We decided to exploit having our own road by me taking charge of the entire right-hand side of the road, and John got all of the left-hand side. We found a decent lunch spot, and sat down directly on the deserted road to eat a second lunch.

We used the tailwind to outsprint a raincloud that we saw behind us during the afternoon, and by late afternoon we’d done almost 200 km and so stopped for an early dinner at a nice little restaurant. We both ordered a local specialty, goulash, which was good and filling.

Back on the road at around 6:30pm, we still had 100 km more to do and were prepared for a bit of night riding. We had a fair climb to do out of town, but the road was well graded and in excellent condition. After summiting, we entered another valley and saw the most awesome sight in front of us – a gentle downhill that went on for what looked like 10 or 15 km. It was truly bike touring heaven, and typified everything that was awesome about riding in inland Croatia.

There were still a few more bumps to do before hitting the next town of Knin, and it was obvious that John was getting very tired, so we planned to stop for more food there (our fifth meal of the day). Coming into town, we spotted the bike of another TCR rider, so pulled over to say Hello. It turned out to be Tim, who we had met at breakfast that morning. He’d been riding the same route as us, and was also refueling before pushing a bit further into the night. He’d found an outdoor fast food stand so we all stood around eating fries and burgers and catching up on stories from the road. Looking at the tracker after the race was done, only about six racers took this route in total during the whole race, so we were very lucky to all be doing it at the same time and to meet up.

It was completely dark once we got going, so we were happy to ride together and have the power of three headlights to see by and three taillights to be seen with, plus chatting made the kilometers pass quickly. Once it was past 11pm, there wasn’t much more being said and we were just trying to get there. We had already decided that we’d sleep rough if we found a good place near Sinj, but I suggested that once we’d done 275 km (which was my new daily goal), then we should look for the next good place to stop.

Neither Tim nor John had a tent, so we needed to find somewhere covered. We found a small village, and saw that the bus shelter was not going to work this time (bus shelters are a very popular spot when doing this sort of touring/race). We then spotted a sign for a church, and all knew that you could often find a place to sleep near those, so headed up the side street. Before reaching the church, we found a small hut by the side of the road. Tim and John went to check it out, and were very excited because it was just a hay store and the flat hay bales looked ideal for sleeping on.

fter reorganizing the hay bales a bit to make a flattish platform, we had a reasonably comfortable bed. John was frustrated with himself because he hadn’t dried out his emergency foil blanket since using it to warm up on the way to the Stelvio pass in the rain. It was wetter on the inside than on the outside, so he turned it inside out, but we weren’t sure about this plan since the foil part that reflects the heat would then be on the outside. By the morning, he’d found out that it wasn’t that effective because he’d had a pretty cold night and hadn’t slept much. Despite the strange location, Tim and I both slept well in our lightweight sleeping bags.

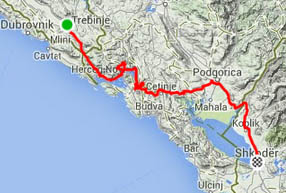

Day 9: near Split (Croatia) – Trebinje (Bosnia & Herzegovina)

| Distance | 249 km |

| Climbing | 2030 m total (8m / km) |

| Moving speed | 23.9 km/h |

| Ride time | 14.5 hrs incl. stops, 10.5 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 7 hrs stopped, 5.5 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

We set the alarm to wake us at 6am so that we could be gone before anyone noticed that we’d slept in their hay barn; it was Sunday morning so we thought that we’d be pretty safe. While packing up and having breakfast, we heard the farmer and his dog herding some goats, so we got a bit nervous, and just as we pulled out of the side-road, the farmer was heading up it on his motorbike, but we don’t think that he realized what we’d been doing there. Tim left a bit of local currency under the string holding together one of the hay bales as a thank you for the wonderful accommodation, so maybe the farmer eventually figured out what we’d been up to.

We were again riding along Croatian backroads without much traffic, and I had spotted an even smaller one that was only on some of the maps that could be a bit of a shortcut. It was a little bumpy and narrow, but we were having a great time exploring this fantastic region. By lunchtime, it started to get really hot for the first time in the whole trip, and we were very pleased to find a grocery store with cold drinks and ice creams before tackling the biggest climb of the day.

My knees and energy level hadn’t been great before lunch, but once we started up the climb, I was feeling great, and was sensing that riding with two other guys was hindering progress a bit because they weren’t always riding as fast as I would and stops always take more time when there are more people. I therefore decided to press on without them. The race rules prohibit drafting (riding directly behind other riders to stay out of the wind), so there is no physical advantage to be gained by riding together.

After summiting on my own, I headed down the really fun, sweeping descent. After going through a village at the top of a ridge, the road went parallel to the top of the ridge for a long time, with magnificent views down to the valley about 200 metres below. Looking at the map later, I realized why the road had stayed up so high for so long before dropping down – we were right on the Croatian-Bosnian border, so the road was made that way to stay in Croatian territory. There was another new section of motorway nearby, so again the old main road was almost deserted.

About 50 km after I had left the other two, I reached the town of Metkovic, where I tried to go into the first grocery store that I found to buy something for an early supper. Unfortunately, it was closed, but just then John and Tim pulled up. We found an open store on the other side of the river and ate together in the riverside park.

After leaving town, we went through the border crossing into Bosnia & Herzegovina and soon discovered that the condition of their roads was nowhere near as good as Croatia’s. We did a 400 metre high climb to get back into the higher inland valleys. I again went hard on the climb and left John and Tim behind. In fact, upon uploading my ride to Strava, I found that I took the “King of the Mountain (KOM)” title for that segment due to having the fastest recorded time; it was my only KOM during the race.

At the top of the climb, I pulled over to go to the toilet, but as soon as I got off the pavement my front wheel hit a rock edge and the tube got pinched and punctured. I had just finished fixing it when Tim and John came by; they had been delayed by taking a wrong turn a little earlier. I therefore decided to stop trying to head off on my own and to ride with them for the rest of the evening. We missed a turn in a small village just after that and took a dirt track to connect to the road that we wanted. Unfortunately, John then punctured on another sharp edge on the dirt track and so we all went to work to fix that quickly and checked that the rest of our tires were well inflated to guard against further problems. Out of the village, the road got smaller and smaller, and we ended up riding along above a dammed lake in an almost uninhabited valley. The concrete road was bumpy, and we were going full speed to try to make up for lost time – I was having a great time trying to keep the same pace as Tim up front.

We did one more small, sharp climb to get into another section of valley, and from the top had a view of a wild, untamed region that felt like we were far, far away from civilization. With the evening light, it was a truly beautiful moment and the “race” element of this ride seemed like a long way away. We had been more in touring mode for this two-day trip through Croatia and Bosnia, and it was two of the most wonderful days of riding that I’ve ever done.

We gave up on our plan to try to get to the coast before stopping, partly because we were worried about doing the big downhill in the dark on roads that may be far from ideal, and so instead set our goal as the next town of Trebinje at the end of the valley. Given our previous night’s accommodation, we really wanted to find a hotel there.

We continued going full gas for the 30 km valley ride into the dark. When we reached town, the hotels were all full and at first they didn’t have another option for us, but eventually found a man who was eating in the restaurant that had a room for rent. Unfortunately, it was difficult to explain to him that we wanted to eat something first before going with him to his place, but he eventually got the idea and marked the location we needed to go to on Tim’s GPS, and we agreed to meet him there later.

While trying to sort out a place to stay, a guy came over to talk to us and asked if we were in the TransContinental Race. We were surprised that someone in this random town in Bosnia knew about it, but he told us that he was actually Greek, and knew of someone from there who was doing the race. Unfortunately, he lived a long way out of town so wasn’t able to offer us a place to stay.

We had been talking about what we were all planning to do next, and it seemed like we would be heading our own ways. John was actually no longer in the race because he had already decided not to climb the Stelvio Pass due to a lingering cold and the terrible weather. He had been talking to his wife frequently, who had been having a tough time looking after the kids back home. So he was planning to find a route home the next day via Dubrovnik. We weren’t far from the third checkpoint, Mt Lovcen in Montenegro, and from there Tim was planning a much more adventurous route than I was: through the mountains to Kosovo and then onto Bulgaria.

Once we got a table at the restaurant, I visited the bathroom, and when I came back, Tim and John had ordered themselves beers, which I was surprised by since they’d discussed earlier in the day how they were both looking forward to Istanbul because they weren’t going to drink any alcohol until then! They weren’t sure if I wanted a beer, so they’d ordered me a Coke, but fortunately I was soon able to change the order to rectify their misjudgment.

After we had some really good pasta (or, at least, it tasted like some of the best spaghetti carbonara that I’d ever had, but that may have been partly due to my state of hunger), I told the guys that I didn’t want to bother going up to the random guy’s room, it didn’t sound too certain that it would work out, and it was definitely going to take a lot of time. I instead headed out to the edge of town and found a place in the bushes to lay out my sleeping pad and bag and slept under the stars. I wished John all the best for getting back to his family quickly, Tim tried to convince me to come with him to Kosovo, but I stuck to what I thought at the time would be an easier route through Albania and Greece.

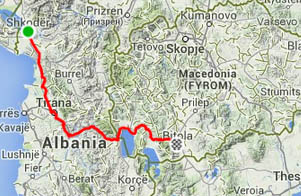

Day 10: Trebinje (Bosnia & Herzegovina) – Mt Lovcen (Montenegro) – Shkoder (Albania)

| Distance | 222 km |

| Climbing | 2550 m total (11m / km) |

| Moving speed | 22.4 km/h |

| Ride time | 15 hrs incl. stops, 10 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 8.5 hrs stopped, 5.5 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

I set my alarm for 5am, so that I could do the climb up to the Montenegran border nice and early. Even before 7am, there was a queue of cars at the border, so I used the time to remove the mudguards from my bike – there was almost zero chance of rain in the remaining part of the ride and they certainly weren’t helping the bike’s weight or aerodynamics.

Once on the Montenegran coast, I found what appeared to be a very large grocery store, but when I went inside, most of the shelves were empty or contained empty cardboard boxes to fill the space and half of the lights were off to save energy. There were some items for sale, just nowhere near as much as you’d expect given the size of the store, so I found enough to keep me going, but it was a rather surreal experience.

I had to encircle the bay of Kotor to get to the base of the climb up to the third checkpoint on Mount Lovcen. It’s known as a beautiful region, but the heat, the holiday traffic and the budget seaside towns weren’t impressing me too much and I was happy to get onto the quiet mountain road where the air slowly cooled down as I gained altitude.

Halfway up the climb, an Italian rider called Mario caught up with me. After trying to communicate in English, which he didn’t speak very well, we discovered that we were both pretty comfortable with French, so we chatted for a while until we found the restaurant that was one of the two possible control points. We went in and got our brevet cards signed by the owner, and I decided to stay for lunch while Mario pushed on. The risotto was good and the view across the bay and over the mountains was really spectacular. I was also very pleased to use the bathroom to get cleaned up a bit after spending two nights sleeping wild.

After lunch, the last part of the climb got a bit steeper and I wasn’t feeling very strong, but along the way a car of four young French tourists passed me a few times as they kept stopping for photos at each look-off. They were cheering me on each time they went past, and near the top I stopped at the same place as them, we chatted briefly, and they insisted that I take a bottle of water from them. They did a great job of keeping me focused on pushing all the way up the climb.

I knew I hadn’t been making great time that day, so when I reached the fork in the road near the top, I decided to forgo the opportunity to do the optional extra kms up to the summit of the mountain, and headed downhill instead. I soon spotted one of the Transcontinental race vehicles outside the hotel that was the second possible control point, and that’s where I found Sam, who I’d last seen on top of the Stelvio Pass.

Reaching the third checkpoint, which was the final really big climb of the whole trip, meant that there would be about four days of riding left to get to Istanbul. I knew that it wouldn’t be simple from here on, but I was now fairly certain that I was going to be physically able to make it, as long as nothing went wrong. Until that point, there had been so much uncertainty about how my body would handle the amount of riding, lack of sleep, and somewhat random eating schedule and diet, that I hadn’t allowed myself to be too confident about whether I would be able to make it.

Accomplishing this goal had become so important to me, I’d been thinking about it ever since following the race the first edition of the race the previous August, and I had been preparing for it in detail since November. I now had so many people following my progress online that it had become an even more important ambition. I was also starting to think about how special it was going to be to see my wife Heather again at the finish line. All of these emotions would sometimes start to hit me, and this certainly wasn’t the first or the last time that it would all start to overwhelm me while riding, and I would shed a few tears to let it all out. I found out after I got to Istanbul that this kind of experience wasn’t at all unusual for many of the other TCR racers, and this is the kind of thing that you can never prepare for, or anticipate how it will feel, or to try to describe properly in words. This race is far more than a physical journey across the continent, but is also an emotional journey, as well as being mentally draining.

When I met Sam at the hotel, we started talking about what was still to come before Istanbul, and I mentioned about my wife and her brother coming to meet me there. Sam tried to ask me something more about this, but saw me getting a bit teary-eyed at the thought of it all, and thankfully decided to leave it there before I got too emotional. I’m glad that when he met Heather at the finisher’s party that he would relate this story to her, because I wouldn’t have admitted to it myself, and it made her realize that I’d never stopped thinking about her during the whole trip.

Getting back on the bike, I still had a third country to reach that day: Albania. The roads out of the mountains towards Podgorica were all generally downhill and fast for quite some distance. As I approached the city, the traffic got a lot denser. I hadn’t ridden in a city since Bolzano in the Italian Alps, and now my adrenaline starting pumping. I was surprised by just how much traffic there was around Podgorica, and it wasn’t until after I got back home that I found out that this is the capital city of Montenegro and almost 200,000 people live there.

I took the major roads that skirted the edge of the city to get onto the road to Albania as soon as possible. I soon realized that the traffic wasn’t giving me any more space on the road than I needed, so I concentrated on maintaining a straight and predictable trajectory, and increased my speed with every passing kilometer. I was almost out of the city, doing about 35 km/h on the flat, when I saw some drain grates coming up that were well below the level of the road surface. Going over them at that speed would be seriously rough, but there were cars coming past at twice my speed who I knew wouldn’t be giving me any extra space, so I couldn’t pull out to dodge around them. I therefore went with option C, which was to maintain my speed and bunny hop the gaps in the pavement. I’ve done this many times before but I hadn’t factored in the extra 5 kgs on the back of the bike, so my hop was effective for the front of the bike, but I didn’t lift the rear end enough and the back wheel came down on the far edge of the gap and the tire deflated immediately with another pinch-flat in the tube.

I pulled over and took my time to install the second of the two spare inner tubes that I’d brought with me and I also had something to eat because it was going to be a few more hours riding yet.

Once at the border, I found Mario again with another Italian rider. They jumped straight to the front of the short queue of cars, so I went with them, and they were able to talk to the Albanian border guard in Italian, which made everything go very fast and smoothly.

We were all planning to find a hotel in the first major town in Albania, Shkoder, which was about 40 km away. There are a lot of Albanians living in Italy, so I decided that sticking with these guys would be a good idea because Italian might be a lot more useful than English in this country.

The Albanian road had been recently repaved and widened and was absolutely perfect, plus there wasn’t much traffic in the early evening. The light slowly faded as we made our way towards Shkoder. We started seeing things that made us realize that we shouldn’t be too complacent while riding on the wide, smooth, freshly paved shoulder – people standing around waiting for a ride, a wild dog off to the side, and then a cart full of hay being pulled by two horses coming straight at us on the hard shoulder. None of these were big problems, we dodged around them and continued to enjoy the riding.

As we got to within 5 kms of the center of Shkoder, it started to get properly dark, but we all had pretty decent lights, so weren’t too worried. However, the road surface then flipped to being quite poorly maintained, without much of a shoulder, the two-lane road became four-lane, and the amount of traffic picked up significantly. Suddenly, we started seeing less predictable driving behavior that made us a bit nervous, and then some things that we’d never seen people do before.

Apparently, the best way to ride a motorbike at night in an Albania city is without any lights and on the left side of the road between the parked cars and the oncoming traffic. We were of course riding with the flow of the traffic on the right side, so these kamikaze motorbikers were coming straight at us with no lights on! We were surprised when we saw the first one, and completely perplexed once we saw the third one and realized that this was typical behavior here. There were also many people on bicycles doing the same thing, but they moved much more slowly and are smaller, so are far easier to avoid than the motorbikes. All the other drivers were making us extremely nervous by their driving style, so we were extremely pleased to make it to the town’s central square to find a hotel.

The first hotel we found was full, we saw a big sign for another a short distance away, but it had five stars, so wasn’t really what we were looking for. I asked my Garmin if it knew of any hotels around, and I was impressed that it had a full list, including one that we hadn’t noticed on the other side of the intersection. The building looked like a very large hotel, but there were no lights on in any of the rooms and there was no sign outside. Mario headed over to investigate while we waited, highly doubtful of whether this was still a hotel and whether it was open. But Mario came out saying that it was all OK, but that I should go in because the receptionist didn’t really speak Italian – English would be better.

The receptionist told me that the price would be 40 euros, which seemed not too bad, although I had thought it might be less, but we were all satisfied. However, we then realized that this was the TOTAL price for all three of us, not the price per person. The two Italians needed to pay 24 euros to share a room and my single would be just 16 euros. We were learning about this country FAST: not only do they have roads that change very quickly from being some of the best to being some of the wildest, but also the prices are extremely cheap.

The room was small and basic, but my shower was divine, finally getting clean for the first time since just after the Slovenian border. I then headed out to find something fast and filling to eat. The restaurants looked like they would take too much time because I wanted to get some sleep, then I saw some stairs down to an entrance that just said “Fast Food” in English – perfect! Having got away with paying in euros at the hotel, it looked like I would need to get some local currency for this place. Taking a quick look at the menu, it seemed that a couple thousand “leks” would be enough to get me through the 24 hours that I’d spend in this country.

I easily found a bank machine, but it didn’t accept my card, so I tried the one next door, which did. Somehow, by the time it came to selecting how much money I needed, my brain had added an extra zero and I asked for 20,000 leks. Back in the Fast Food restaurant, I ordered a cheeseburger, fries, drink, and something sweet, and the guy told me that the total cost was “five”, so I gave him five 1,000 lek bills. He laughed at this, and the customers at the nearby table also found it funny, and that’s when I realized that he meant five HUNDRED leks (about 3 euros) and not five thousand leks (about 30 euros). Obviously, I had a lot more to learn, and I might not be able to spend all of my 20,000 leks in the next 24 hours.

This was the start of my sprint to the finish along the main roads of Albania, Greece, and Turkey. It wouldn’t be the most enjoyable four days of riding in my life, but it would certainly be eventful and unforgettable.

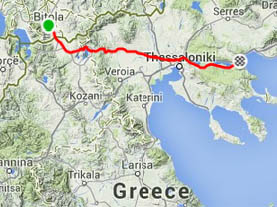

Day 11: Shkoder (Alabania) – Tirana (Albania) – Bitola (Macedonia)

| Distance | 319 km |

| Climbing | 2860 m total (9m / km) |

| Moving speed | 24.4 km/h |

| Ride time | 16 hrs incl. stops, 13 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 9 hrs stopped, 6 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

I’d set my alarm for 5am, to be on the road by 6, shortly before sunrise. In the end, my alarm wasn’t needed because at 4:45am the minaret on the nearby mosque started blaring out the call to prayer from the speakers that were impressively loud. I can’t imagine that many locals really appreciate this early morning wake-up call every day, but it was perfect for me.

Having ridden into Shkoder on a section of wide and freshly-paved road, and then experienced the craziness of the city streets, I was eager to find out what the road on the other side of town was like. Unfortunately, it hadn’t been improved at all, but since the early morning traffic was light, I decided to stay on the main road after Lezhe instead of taking a less direct route on smaller roads. In hindsight, this was probably a mistake. The traffic increased significantly and although the road was often wide enough or had a bit of a hard shoulder so that I could ride along without being too bothered by the constant passing traffic, occasionally the road narrowed significantly.

The small rear-view mirror that I’d installed in the end of my handlebars more than proved its worth. I installed it just before leaving London because I was experiencing some discomfort in my neck that made turning my head to see the traffic behind me a little difficult. In the end, my neck wasn’t a problem at all, but having the mirror was essential on these types of roads because I had to keep my eyes on the road ahead to hold a dead straight line in the little space on the road that was left while at the same time keeping an eye on what was coming up behind.

The worst moment was when I saw a truck approaching in the oncoming lane, and one coming up from behind and I knew that there wasn’t enough space for us all given the width of that section of road. I therefore went onto the dirt on the side of the road until there was space to get back on. A couple kms later, I found another racer who had just finished repairing front and rear punctures. He said that an oncoming bus had decided to pull out to overtake a truck, and so there was no more space for him on the road, and he’d turned onto the gravel pretty fast and hit something hard that had caused both tubes to puncture.

In addition to the road not being wide enough for the volume and speed of the traffic, there was also the terrible condition of the road surface to deal with. The bridges were especially bad, and in one place all of the traffic suddenly slowed down because the bridge had bumps and gaps that were so violent that no vehicle wanted to do more than 10 km/h to get over them.

It was obviously time to get off of this awful road, so I planned to take the next minor road that linked up with the backroad that I wanted. Just before I got there, the overly narrow highway widened abruptly to now have two lanes each way, a dividing wall in the middle, and a wide hard shoulder. I then saw a no bicycles allowed sign, so I decided to stick with my new plan to get off of this road. However, that next section of divided highway with a shoulder was probably twice as safe as the previous section where the road was too narrow for cyclists to have a safe place to ride.

Riding along the backroad was nice because I got to see some of the life in the small villages that I passed through, but after a few kms the road deteriorated, first with massive cracks and potholes appearing, then it turned into a gravel road, and then just dirt that had been half washed away by small streams. It was one of the bumpiest roads that I’ve ever ridden with a road bike, and although I could dodge most of the big dips and holes, I got caught out a few times, and did have one water bottle go flying out of its holder, but nothing more serious. At least there were almost no cars using that road because of the terrible condition and those that were using it were barely going any faster than me, which was about 15 km/h – half of what I’d been doing on the highway.

This ‘road’ is shown on maps as being a reasonably major route, and the only option other than the insanely scary highway. By this time, I was not enjoying my experience of Albania one bit. Based on what I’d read before going, I had been more worried about cycling in Albania than in any of the other countries on my route, but it was turning out to be far worse than I’d imagined. It wasn’t just the condition of the roads or the wild and dangerous behavior of the drivers that was bothering me – it was the other parts of the culture that I was experiencing that were not endearing me to the place.

One thing that reflects the country’s status of one of the poorest nations in Europe is the number of stolen cars on the roads. Even the mayor of the capital city, Tirana, admits this, as he said the following when talking about the old, half-broken cars in the city that help to make it the most polluted capital city in Europe: ‘Most of the cars in Albania are stolen; no one knows how many there are and where they come from.’ I would say that knowing where they come from is not difficult, because they tend to leave the old German and British license plates on, seemingly to show off the fact that the car was stolen.

Despite the poor condition of many cars mechanically, the Albanians LOVE to keep the outside of their cars spotless. Every small town is full of teenage boys on the side of the road advertising their services to wash the rich, old men’s stolen cars. The obsession with clean cars was in sharp contrast to the amount of trash that was all over the place. Apparently, trash collection services simply do not exist in many parts of the country and so the sidewalks and roadsides are often covered in trash bags and rubbish.

One more thing that was a particular problem in Albania, but which is also partly true of the other countries in the region, is that there are lots of wild dogs around who like to chase cyclists. One other racer told me of being chased by a pack of around 20 of them while riding at night in Albania! Fortunately, I only had a couple of Albanian dogs give me a half-hearted chase as I went past the property that they obviously lived at, so were not actually wild.

Another serious hazard in Albania is the man-hole covers, or lack thereof. The value of the metal in a man-hole cover makes it worth stealing almost every last one of them, so there are gaping holes in the roads and on the sidewalks in the towns and cities. The holes can easily be more than half a meter across and several meters deep, see the photo on the right. You better keep your eyes open when walking or driving, especially at night!

If this wasn’t enough problems for one country, I’ve also read that there is a massive mafia problem, that the security of elections is not that great, and the factories do almost nothing to prevent polluting the air, water, and soil. Overall, I recommend that you never visit Albania – the place is a mess in so many ways, people seem to have no respect for their land or their own health or safety.

After about 10km of riding on the dirt road, I made it back onto the highway to get into the capital city of Tirana. It was the only sensible way to get there and at least by then the traffic heading for the coastal towns and the airport had turned off. There was a decent-sized shoulder, but 100% vigilance was required at all times because I never knew what hazard would pop up next or what the drivers around me might decide to do. I used all of the city riding skills and experience that I’ve accumulated over the years to get out of the city safely – it certainly wasn’t for the faint of heart or inexperienced.

I did have one problem when approaching Tirana, my third pinch flat of the trip that I picked up by again only being able to bunny-hop the front wheel over a major crack/gap in the road, the back wheel not quite making it. I was out of spare tubes, but I repaired one of the previously punctured tubes with a pre-glued patch that I had and got back on the road reasonably soon.

Fortunately, once out of Tirana there is a brand new motorway with a big tunnel under the mountain so that the old main road that goes over the mountain was almost empty. I finally got to enjoy the scenery and relax a little. It was lunchtime, so I took advantage of the cooler temperature at the higher altitude and stopped for lunch under a shady tree with a nice view.

Once over the mountain, I had to go up a long valley that slowly climbed for 70 km to a mountain pass at 1000 meters altitude that is the border with Macedonia. I wanted to get out of Albania as soon as possible, so I was extremely pleased to have a massive tailwind blow me up the valley at an impressive speed.

The climb was mostly gentle until the last few steep kms. I had great fun racing up the switchbacks of that section while trying to stay ahead of a big clapped-out old truck that was having a hard time gaining on me even though I was only doing 10-15 km/h. He gave me a big thumbs-up when he eventually got past.

At the border, I was in line between two cars from Poland. They were full of young guys on a road trip around Europe. They thought that what I was doing was very cool, and took some photos of me and the bike. After the border, they caught and passed me as I was doing about 60 km/h on the descent. One of the guys leant way out of the window to wave vigorously and take some photos as they went past. The wind caught his sunglasses and they flew off and smashed on the road. When he realized what had happened, he roared with laughter and told his buddy to keep driving. They seemed to be having a great adventure!

I would never ride in Albania at night, but I was now entering Macedonia with about 1.5-2 hours of light remaining and wanted to look for a hotel in Bitola, a town that was about 3 hours of riding away. The only other town with places to stay was less than one hour away. I therefore had to figure out what Macedonian roads and drivers were like before reaching that town so that I could decide whether it would be safe enough to do some night riding. Fortunately, Macedonian drivers seemed to be a lot less aggressive than the Alabanians, and the roads from the border down to Lake Ohrid were all in a decent condition and well made to handle the moderate amount of traffic, so I decided to push on.

I didn’t see much of Macedonia, only doing about 100 kms across the southwest corner of the country, and spending about 12 hours there in total including my hotel stay. Even so, I really enjoyed the experience: The high-altitude lakes of Ohrid and Prespa were very scenic, the forested sections of hills that I went through between each valley reminded me of riding in parts of Austria, and the vibe of the packed outdoor restaurants in Bitola that I walked through on the way to my hotel was really cool. I felt like I was back in a somewhat familiar landscape and culture and I was very pleased to leave the unfathomable land of Albania behind.

I did almost 320 km and 3000 meters of climbing that day. It was the second biggest day of riding during the trip, with only Day 2, when I got off of the ferry in Dieppe, France early in the morning, being more distance. However, the ride from Dieppe was far easier, with 1000 meters less climbing and on roads that were a lot less stressful to ride on (despite riding 50 km across Paris that day). I was extremely satisfied by having reached Bitola because it meant that I was now back on schedule to arrive in Istanbul on the 14th day.

Day 12: Bitola (Macedonia) – Thessaloniki (Greece) – Asprovalta (Greece)

| Distance | 259 km |

| Climbing | 1110 m total (4m / km) |

| Moving speed | 25.5 km/h |

| Ride time | 14 hrs incl. stops, 10 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 9 hrs stopped, 6 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

I got up early and was on the road just before sunrise. The Greek border was about an hour away, and shortly after passing through I found a small grocery store where I bought my second breakfast as my energy levels were pretty low.

I had a short climb to do afterwards, which was nice as it got me onto quieter roads. A couple of farm dogs decided to chase me near the top, I wasn’t too worried about them but one jumped up at the back of my bike and knocked my rear derailleur into my wheel. This startled him and they both ran off, but my wheel now wouldn’t turn as a spoke was broken. I walked up to the top of the small rise to fix the bike, where there was a shrine with a stone bench.

Fortunately, I’d brought a couple of spokes of each length and the tools needed so that I could fix such problems and my rear wheel uses straight-pull spokes that can be replaced without removing the cassette, which makes the job much easier. I couldn’t get the wheel perfectly true, but it was good enough. I also had to replace a damaged link of the chain with a quick link. This was a pretty major repair to do on the road, and I was pleased to have brought everything that I needed to take care of it.

I gradually made my way out of the higher lands on a large road that had very little traffic. In the town where I planned to stop for lunch, I spotted another TCR rider having an ice cream. It was John Duggan, better known as JD, who I hadn’t seen since we chatted at a petrol station near Sargans, Switzerland. We shared stories of being chased by dogs before he carried on and I found a restaurant.

In the afternoon, I found a large grocery store, so filled up my bags and bottles with food and drinks, but what I really wanted to find was a sports or bike shop where I could re-stock my depleted stock of inner tubes. I spotted one shop with many bikes displayed outside, but was very disappointed to discover that it was a toy store, so the only tubes they had were for kids’ bikes and mountain bikes.

I was approaching the big city of Thessaloniki, so the highway got bigger and busier, with parts of it reminding me of Albania as the hard shoulder appeared and disappeared abruptly, but again there was no other decent option available. This was a city in which all the riders who went through it found different routes. I didn’t want to go into the center of the city and back out, as many people did, and I also wanted to avoid riding on the ring-road around the north side of the city because that would be far too be busy and unsafe, although many others did so. I’d found a route during my planning that weaved through the industrial estates north of the city, but I wasn’t very sure whether it would actually be possible. In the end, it worked out exactly as I’d planned, and I was extremely pleased and proud of my planning when I made it onto the road going out of the city that I wanted.

From there all the way to the Turkish border almost 400 kms away there was an ideal road to ride on because the old main highway had been recently superseded by a new motorway. The first part of the old highway wasn’t quite as quiet as I’d hoped, but it was still nice and wide and safe.

I rode past a couple of large lakes, and by the time I got to the coastal resort of Aspravalta it was getting dark. Despite it being mid-week, every hotel I asked at was full, so I resigned myself to wild camping on the edge of town. Luckily, it was easy to find a grocery store and a pizzeria on the main street to restock my supplies and get some hot, filling food.

Day 13: Asprovalta (Greece) – Alexandroupolis (Greece) – Turkish Border

| Distance | 297 km |

| Climbing | 1250 m total (4m / km) |

| Moving speed | 25.9 km/h |

| Ride time | 15 hrs incl. stops, 11.5 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 10 hrs stopped, 6.5 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

The early morning ride followed the coast of the Thracian Sea for some time, with many fantastic views. The peaceful ride was only interrupted by a ticking noise coming from my chain, so I finally decided to stop and investigate.

When waiting for the ferry from England to France, I had met a rider called Chris Bennett. We spent a while talking about equipment, routes, etc., and I was impressed because he seemed to be very prepared for everything that was about to come and was experienced at this kind of event. We also had the same goal of reaching Basel in two days from the ferry, so I’d been keeping an eye on where he was on the tracker. He hadn’t quite made that goal (mainly due to route-finding issues), and I’d been slowly getting ahead of him until he took the shorter route down the Italian coast to take the ferry to Split instead of going overland through Slovenia and Croatia like I had.

When I got to the top of the third checkpoint at Mount Lovcen in Montenegro, I saw that he had passed through 12 hours before me. Since then, it had been my goal to catch him before Istanbul. He’d stayed in the same town as me the previous night, so it had only taken two and a half days to catch him.

It was therefore not a big surprise to see Chris come along when I was investigating my chain noise. He was now riding with Rickie Cotter, a very funny and tough Welsh lady. I’d found that I had two more chain links coming apart, but due to using one of my two spare quick links the previous day, I only had one left. I therefore decided to try to fix both links instead of replacing them and hope that at least one would hold (not an easy task with a narrow 11-speed chain). However, getting the links lined up again was not proving so successful. So Chris had come along at the perfect time because I could use his mini pliers to get the chain realigned before using my chain tool to pop the pins back in place. I’d decided to do without a pair of pliers for this trip, but have since found some lightweight miniature ones that I’ll take with me on future trips.

Chris and Rickie left me fixing the chain while they pushed on. After another 50 km, I stopped at a bakery to get some food and had another check on the chain. One of the links that I’d repaired was holding together perfectly, but one had come apart again. I therefore used the remaining quick link to replace the broken link and left the other, which fortunately held up all way to Istanbul.

Heading towards the town of Kavala, I saw an awesome sign – the first one with ‘Turkey’ listed as one of the destinations. It really felt like I was getting close to the finish line now. I stopped by the side of the road and took a picture of it. Apparently, I was not the only person to be excited by this sign because when looking at other people’s ride reports I’ve seen multiple pictures of the exact same sign taken independently by different riders, which made me laugh very hard (see the photo montage on the right).

I was planning to get to the town of Xanthi before stopping for lunch, but my rear tire went flat again shortly beforehand. I found a shady bus stop to sit in, eat lunch, and repair the tube. The problem this time was that the pre-glued patch was no longer airtight, so I repaired another of the punctured tubes instead. Just as I was finishing, Chris and Rickie came by, but I told them that I was OK and they carried on to find a restaurant.

On the other side of Xanthi, my rear tire went flat AGAIN. I was getting seriously frustrated by now because I really wanted to make up time, and I was feeling strong, but the fourth mechanical delay of the day meant that I was falling further and further behind schedule. I don’t remember exactly what caused this, my 5th puncture of the trip, but I was soon able to get going again and so went full gas for half an hour to make up some time, but was very worried because I’d used up all of my tubes and patches.

The afternoon was hot, and by the end of it I was feeling pretty depleted of energy and overheated. There was one climb up to around 250 meters altitude before getting back to the coast at Alexandroupolis. The climb would normally have been no problem, but I really struggled on it.

Heather had posted on Facebook a day or two beforehand that people could send me text messages, and I received many messages of support, which was great. I didn’t respond to them at the time, but while struggling with the heat and climb one came in from Alan Edgar asking how it was going. I was happy to take my mind off of the conditions by writing a response, and the short exchange brightened my mood.

Unfortunately, Alan neglected to mention what had spurred him to text me, which was that my tracker was no longer transmitting. Apparently, there were dozens of people watching their computer screens and wondering why I was stuck in northern Greece, fearing the worst, when in fact it was just the tracker batteries that were dead. I wouldn’t know anything about that until I spoke with Heather that evening.

I found a couple of local road cyclists, which was something that I hadn’t really seen since Italy. I stopped each of them to see if they would sell me an inner tube or a patch kit. The first one had no spare tube and wouldn’t sell me his patch kit; the second one was not carrying anything with him, so I nervously kept going, praying that my tubes would hold up.

Once I was through Alexandropoulis, the sun was starting to go down. I therefore decided that I would get past the Turkish border that evening and then look for the first hotel instead of trying to push on to the next town (again, I wasn’t keen on riding at night in a country that I hadn’t yet got to grips with in terms of driving behavior and road conditions). Fortunately, there was a hotel in the middle of nowhere just on the Turkish side of the border. It was an odd place, part nightclub, part hotel, but I negotiated a decent price for a good night’s rest. Before going to bed, I phoned Heather, who had just arrived in Istanbul with her brother, and she was able to research where there was a bike shop in the next major town.

Day 14: Turkish border – Istanbul (Turkey)

| Distance | 301 km |

| Climbing | 2520 m total (8m / km) |

| Moving speed | 25.2 km/h |

| Ride time | 16.5 hrs incl. stops, 12 hrs moving |

| Previous night | 9 hrs stopped, 6 hrs asleep |

| View on Strava | |

I was excited to start what I hoped would be the last day of the race, so I again got on the road half an hour before sunrise. The road was nice and calm for a while, but the traffic soon started to pick up. Whereas in Greece, they have built a new motorway that runs mostly parallel with the old road, so that the old road is generally nice to ride on, in Turkey they are instead upgrading the old road into a motorway, leaving no other alternative. They were still finishing one side of the motorway in some sections, so the road width was greatly reduced for several kms. I went as hard as I could through these narrow sections to minimize my time on them and reduce the number of cars that needed to pass me there.

Having learned about the dead tracker batteries from Heather, I implemented plan B, which was to connect it to the USB port of my dynamo hub, which I’d used throughout the trip to keep my Garmin and phone charged. I was pleased to hear that it worked because I hadn’t tested that setup beforehand.

I had an early lunch in the city of Tekirdag after 100km of riding, at a beach-side fast food place. I had been making good time and was hopeful of reaching Istanbul by early evening. My tires and tubes hadn’t had a problem for more than 250 km, and I only had 180 km more to do. So instead of heading into the city to find the bike shop that Heather had researched for me, I decided to risk it and keep pushing on.

Shortly after Tekirdag, I found Chris and Rickie again, who were planning to take the exact same route as me, so I knew that as long as I stayed ahead of them then I would be able to get a new tube or patch if I needed it. We stopped at a gas station to get something to cool us down because the temperature was over 30 degrees. I was amused that they chose the exact same thing that I and all of the other racers that I’d been with at other similar stops along the way had chosen – a Magnum ice cream and a bottle of Coke. Who needs scientifically tested energy bars and sports drinks, when Magnums and Cokes can get you all the way to Istanbul? Chris had even set himself a challenge – to eat 10 Magnums in one day! Within about 15 minutes, he ate Magnums numbers 4, 5, and 6. When I saw him at the finish that evening, I was disappointed to hear that he’d only made it to number 7.

Unfortunately, after Tekirdag the road got busier and busier. It’s hard to describe this type of road because it’s not like anything in western Europe. It’s a divided highway with two or three lanes going each way, and with vehicles doing motorway speeds, but also some old trucks that struggle to go anywhere near that fast. There is a hard shoulder, but because there are no exit or entrance ramps and there are businesses, houses, and roadside stalls all along, the hard shoulder can be used at any point by vehicles joining or leaving the road. Occasionally, there are massive intersections controlled by traffic lights. I saw that if drivers want to get past a group of slower vehicles ahead and the light is red, then they sometimes drive up the hard shoulder to the stopping line and wait for the light to go green. Once green, they floor the accelerator and get past all of the other vehicles. The hard shoulder is also used as the bus stop, so there are many pedestrians hanging around on it, and cars also drop off and pick up people all the time. Riding along the hard shoulder is therefore a real test of vigilance and bravery.

I made it about half an hour down the road after the gas station before my rear wheel went flat again. It was another pre-glued patch that had failed – maybe it was the heat that they didn’t like? I had nothing left with which to repair it, but I knew that Chris and Rickie would be along soon. Thankfully, Chris had extra vulcanized patches and a tube of glue that he donated to me before pushing on, so I took my time to do the patching job well and vowed to never use a pre-glued patch again.

It was less than an hour before my next rear puncture. This time it was a large piece of metal wire that had pierced the tire. JD came past when I was fixing it and we talked for a while. I also noticed that the tire was damaged from where I had one of my pinch flats, so I reinforced the inside with an emergency tire boot (basically, a stiff piece of material that prevents the tube from rubbing against or pushing out of any hole in the tire). I also found a small piece of glass embedded in the tire that hadn’t made its way through to the tube yet, so it was good that I removed it then.

During one of these stops, the tracker lost power for long enough that it shut down. I hadn’t been checking this since I had far more important things to deal with and the tracker is a minimalist, stealth model so it doesn’t have an external power light. If somebody had sent me an SMS to tell me that the tracker wasn’t transmitting then I could have fixed it by simply pressing the button once I got moving again, but no-one thought to tell me, and instead those that were trying to watch my progress started worrying again, so I apologize for that.

I eventually reached the turnoff from the highway to head for the obligatory northern route into the city that would be much quieter. I knew that there would be a bit of a climb when heading away from the coast, but the strong headwind was not something that I’d anticipated. The punctures had put me well behind schedule and I’d now be arriving in Istanbul in the dark. I was starting to feel my energy dropping quickly because I’d been riding hard whenever the bike was functional. I wanted to keep pushing all the way to Istanbul, but knew that I only had a few snacks left in my bags, which probably wasn’t going to be enough because I hadn’t eaten much all day and I still had almost 100 km to go.

Near the top of the climb, I spotted a small restaurant, so I decided to stop for a real meal. It was the only time that I hadn’t taken the decision that was optimal in terms of not wasting any time since the third checkpoint in Montenegro four days before, but it somehow felt right to have a final meal and enjoy the feeling of having almost made it. Or maybe I just wanted to prolong this adventure a little bit more and didn’t want it to be over quite yet.

The waiter spoke no English, but he got the idea that I needed something good and filling and sorted it out for me. He also led me to the bathroom because I apparently needed to get a bit cleaner before eating. I’d been on the road all day, fixing flats on the side of the road in the dust and dirt, had a bloody lip that hadn’t healed for the last week, and hadn’t shaved since Switzerland, so I was looking pretty rough. I sent Heather an SMS telling her that I was stopping for dinner and might look a bit feral when she saw me later that evening.

I soon spotted JD coming up the road. I’d passed him at the base of the climb, and he looked like he had even less energy than me. I called him over and suggested that we ate together, and we quickly doubled the order of whatever I was getting.

The food was fantastic, very filling and cost very little. It was far more of an authentic Turkish dining experience than any of the restaurants that I’d visit with Heather and Daniel in Istanbul in the following days, and we paid less than half of what the Istanbul prices were. It was the most memorable meal of the whole trip and it was especially nice to have JD there to share those last special moments of the race with.

Being fully refueled, I was ready to go full-speed to the finish line in Istanbul. In contrast, JD was thinking about camping wild somewhere and then finishing the ride the next day, so I headed off without him. The northern route into Istanbul started on a reasonably small road, but it soon changed into a big highway that had just been built, but had very little traffic.

I was still pushing hard on the pedals as I went up some fairly long, gradual climbs, and I was amazed by how strong I was feeling after all of the kms that I’d done in the previous two weeks. With less than 50 km to go to the finish, I started to think that I might make it without any more problems, but then my back tire went BANG, and I was pretty sure that I’d ridden over something sharp that had cut the tire and tube.

I’d already used my only tire boot to repair the damage caused by an earlier pinch flat, but Chris Bennett had insisted that I take a second one when he gave me the patch kit earlier in the day, which was exactly what I needed to cover the hole in the tire; I then went to work on patching the tube. The evening light was fading so I only had one chance to get it right before darkness fell, so I was very relieved that it worked perfectly first time.

This was the ninth puncture of the trip (one or two may not have made it into this report for the sake of brevity), eight of which had come within the previous 1000 km, and six of which had been entirely independent of each other (i.e., not caused by a patch failing or something staying in the tire and causing multiple punctures). My tires (23mm wide Michelin Pro4 Endurance) have excellent longevity on decent-quality roads, but were not up to the conditions that I found in southeastern Europe. Unfortunately, even though I had wanted to use some wider and possibly sturdier tires, because of the frame clearance and the mudguards/fenders that I was thankful that I’d had for the first week of the ride, I couldn’t fit anything else. If I do this again then I think I’d take a different bike that had more clearance to take sturdy touring tires as well as full fenders.

The tube that I had now hopefully fixed had three patches and the tire had two boots for extra support. The chain had two quick links and a bodged repair job on a third link. The rear wheel had a replaced spoke and wasn’t all that true. My two rechargeable front lights and one rear light had all stopped working a while ago, one because of the charging adaptor being unreliable and the other two hadn’t worked since the rain in the Alps. The rear dynamo-powered light had a dodgy connection which I had to keep checking because it sometimes started to flicker, and could even go out (fortunately, my dynamo-powered front light had no problems). The rear derailleur worked, but was far from perfect ever since the dog knocked it into the spokes because where it was connected to the frame was slightly bent. The satellite tracker was no longer working due to the flat batteries. The rear brake pads were getting close to being down to the metal support, so I was preserving the back brake by using only the front brake when possible. My right shoe had a buckle that worked backwards because the original broke in Montenegro and the spare that I’d brought was for the other side.

None of these problems were stopping me from riding, which is why I hadn’t fixed them (although I did have spare brake pads and a derailleur hanger with me if I really needed them), but when all of these were added together, the bike was limping towards the finish line. If I didn’t have all of the bike repair knowledge and experience that I’d gained over the years, I’m not sure that the bike would have made it, or at least not without causing me major delays.

I had to do one short climb through a forest to get to the Bosphorous river and then the final stretch to the finish line. Once I was within 10 km of the finish, I knew that no matter what mechanical issues I had with the bike, I would be able to walk the bike to the finish line, so that no longer worried me. I was only concerned about a crash that would prevent me from continuing, so I took the final descent through the dark forest and the ride along the Bosphorous extremely cautiously.

I was very pleased to make it to the finish just before 10pm, because that was exactly 13 days and 12 hours since leaving London. However, I missed the café the first time past, so had to turn around and officially arrived there two minutes after my 13.5 days goal. I had thought about how special it would be to finish many times during the race, but now that I was here it seemed odd and far from overwhelming (I later learned that this was a sentiment shared by many racers). Even so, it was wonderful to see my lovely wife, give her a big hug, and also her brother Daniel.

I was very surprised to see Tim already sitting in the café because when I left him in Bosnia, he was planning a far more adventurous route than I was, which I was certain would take much longer. He’d even pushed his bike up a mountain track for several hours in the dark to get into Kosovo, then pleaded with the border guards to let him through even though the crossing was officially only open to local residents. Somehow, he’d managed to get there faster than me despite all of that!

Chris and Rickie came in not long after me having also had major puncture problems caused by Rickie’s dodgy rim strip. Then JD arrived, having decided not to sleep with the wild dogs in the forest, but to instead find a hotel in Istanbul. At the finisher’s party the next evening, I got to speak with many of the other friends that I’d met along the way, all of whom were wonderful people. The feeling of camaraderie and respect between the racers was immeasurable.

Overall, this trip was a wonderful, satisfying experience that will stay with me for the rest of my life. I experienced many great moments of beauty and enjoyment on the bike, which more than made up for the hardships and negative experiences. Unfortunately, many of the negative experiences happened within the final four days, as described here, but it was a shame to end with those because the rest had generally been so fantastic, and I prefer to remember it for those truly wonderful moments.

Summary Statistics & Results

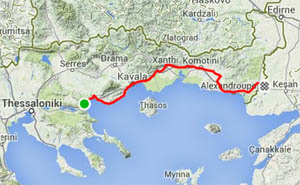

The map on the right (click to enlarge it) shows my complete route, with the start, finish, and intermediate checkpoints marked in green and overnight stops marked in blue. More detailed maps for each day are shown with the daily descriptions, so click on the links above to see those.

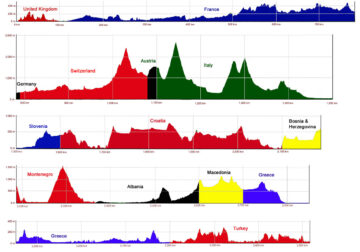

The map only shows two dimensions, so the second figure shows the third dimension, elevation. Please note that the scale on the y-axis differs between each section of this figure, as otherwise the sections with large mountains would cause the other sections to appear completely flat. The 14 countries that I passed through are shown in different colors.

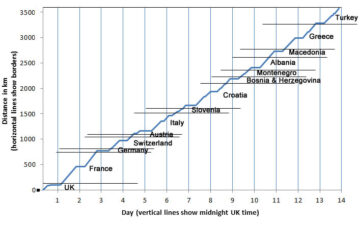

The fourth dimension is time, which is shown in the third figure where my progress in kms is plotted against time on the x-axis (measured in days, with the vertical lines showing midnight UK time, which is 10pm in Istanbul). Sections where the line is flat shows when I stopped and for how long; only stops of at least one hour are shown. Horizontal lines show country borders.

The values shown in the figures are not overly precise, the actual totals were 3,592 km (2,232 miles) of total distance with 31,000 metres (100,800 feet) of climbing in 13 days 12 hours elapsed time, at an average moving speed of 23.6 km/h (14.7 m/h).

The first day was unusual because I only did a short 100 km ride and then had to wait around for the ferry for the afternoon and evening, so I have included that day in the totals above, but not in the averages below.

My average daily distance was 268 km (167 miles) with 2200 metres of altitude gain, which I completed in 15 hours of elapsed time, 11.5 hours of that being on the bike (so 3.5 hours of breaks during the day). At night, I stopped for an average of 9 hours, of which I slept for about 6 hours (with the shortest sleep being 2.5 hours and the longest 8.5 hours).

Day 2, in France, was my longest, managing 360 km (224 miles) in 15 hours of riding and 18 hours elapsed time. Day 5 was my biggest climbing day with 4300 metres of accumulated altitude gain across the Swiss, Austrian, and Italian Alps. I twice managed to average 26 km/h (16 m/h) for the day, on Day 3 in France for 306 km and again on Day 13 in Greece for 297 km. My best 4-day period was the final four days in which I did 1176 km, or 294 km/day, with an average speed of 25 km/h.

The race results are on the official race website. I analyzed the data to breakdown how I did, and here are my placings:

- 87 people started the race in London.

- At Checkpoint #1 in Paris, I was 30th; 83 of the riders made it to that checkpoint.

- At Checkpoint #2 at the Stelvio Pass, I was 26th; 74 people made it that far.

- At Checkpoint #3 in Montenegro, I was 48th; 70 people reached there.

- At the finish in Istanbul, I was 32nd of the 64 finishers (and 87 starters).

I was relatively slow between checkpoints 2 and 3 because I took the overland route through Slovenia and Croatia rather than using the faster Ancona-Split ferry across the Adriatic. Looking at the times for only this segment, I was 57th of 70. Based on everyone else’s times and a bit of linear regression analysis, taking the ferry (which 41 of the 70 people did) appears to have saved about 20 hours for people going at my speed. However, even if you make some corrections based on who took the ferry and who didn’t then I’d still only be about 48th of 70 for that segment because that’s where I went into bike touring mode and enjoyed the ride through the region instead of racing. Indeed, that section is where my fondest memories of the whole journey are from.

My fastest section relative to everyone else was the final stretch from Montenegro to Istanbul: I was 18th out of 64 when looking at that section alone. That was despite all of my mechanical problems occurring then, which shows that I wasn’t the only one having difficulties and that I was still able to keep riding strong all the way to the end.

The winning man was Kristof Allegaert, from Belgium, who finished in 7 days 23 hours, which was 31 hours ahead of the second-place man, Josh Ibbett, from England, and two hours ahead of the race organizer arriving at the finish line in the official vehicle! The first woman was Pippa Handley, who finished in under 12 days and 5 hours. All three of those took an overland route. Pippa and I had been quite close at several points during the first half of the race, but then she really took off and finished 31 hours earlier than me.

This page is in the My Bikepacking Race Reports section. The next page in this section is: