Bikepacking and ultracycling races consist of cycling for long periods at low power levels, so how much and what type of structured or unstructured training and training plan is suitable when preparing for such events?

Page Contents:

This page focuses on how to physically prepare for bikepacking races and what a typical formal or informal training plan might consist of. There are many books and websites with advice on how to train to be a physically fitter cyclist in general.

Although many of the questions and answers presented here specifically mention The Transcontinental Race, similar advice applies to training for most ultra-distance cycling races.

Q: When should I start training for a bikepacking race?

How long before a given event you should start training specifically for it depends on what level of fitness and experience you already have. As a general guideline, if you already have a reasonably solid base to work on, then 6 months may be enough to get your body in shape and learn the basics of the Mental Approach & Strategy that you’ll need to do a bikepacking race.

If you’re really new to ultra-distance cycling, touring, or bikepacking then you may need to take one or two years to build your condition and gain enough experience before attempting an actual race. In contrast, some people who already had a lot of experience and fitness have entered bikepacking races after only finding out about them a couple of weeks beforehand and were able to get ready in time to complete the race successfully, but that won’t be possible for most people.

A: Between 2 weeks and 2 years.

Q: How many kms / miles should I do in the months leading up to a bikepacking race?

Again the answer depends on the person. At the extreme top end of the scale, Kristof Allegaert, three-time winner of the Transcontinental Race (TCR), has said that he rode over 20,000 km in training in the 7 months between the start of the year and the race. In addition, Melissa Pritchard, who won the women’s category of the 2017 TCR, rode over 15,000 km in training in that same time.

However, most people would be very pleased to get close to even half of those lofty figures. Based on informal chats that I’ve had with other TCR racers, doing about 5,000 to 10,000 km during the six months before the TCR seems to be quite typical, with less in the winter (500-1000 km per month) and more in the spring and summer (1000-1500 km per month).

Although I know some people who already had a solid base of cycling fitness and experience that successfully completed the TCR after riding less than 2,000 km in the six months before the event, I wouldn’t recommend that approach, especially not for anyone who is lacking experience.

Many races create Strava groups for participants to join and see what training other people are doing, and there is also a Ride Far Strava Club. However, be careful when comparing yourself to people on those weekly leaderboards because the people most likely to join the groups are the ones who are doing the biggest distances, and each week there will be some people doing massive distances, but those are normally not the same people every week, so they are not a good indicator of what YOU should be doing.

A: Between 2,000 km and 20,000+ km in the six months leading up to the event.

Q: Do I need to use a structured training plan?

This is again dependent on the rider, but if you decide to make a training plan then I highly recommend making monthly distance targets rather than weekly targets. My riding varies quite a lot from one week to the next based on when I schedule bigger rides, what is going on in the rest of my life, the weather, etc., so I would find a weekly target very hard to stick to; in contrast, my monthly totals tend to be pretty consistent and so that is the only thing that I pay attention to.

Some people prefer to do structured training rides with interval sessions, etc. I prefer a more relaxed approach, but because the region where I live in Switzerland is far from being flat, the frequent climbs tend to induce a natural variation in the amount of exertion that I put out during a ride. Interval sessions may therefore not give as much of a benefit for me as they would for someone who lives in a flatter region, and some people find interval work to be an excellent motivator.

I choose my training routes based on how hard I feel like working on a given day – sometimes challenging myself on a hilly to mountainous route and sometimes taking it easy on a flatter route. When I really want to push my limits, I go out with the local group of fast boys who take off on every climb and also go full gas on many of the flatter stretches. That forces me to work far harder than I ever would when riding alone, and I do somewhat enjoy just about keeping up with them.

Personally, I very rarely do “training” rides; I mostly ride because that is what I love doing, because I need to get somewhere (I choose to not own a car), or I want to see a new place. Fortunately, training is a helpful side-effect of this addictive past-time and choice of transport. If you can make cycling a habit rather than a chore then the training will come naturally.

Cycling to where you work, study, etc. is the most time-efficient way to log more distance because you’d otherwise be wasting that time sitting in another form of transport. Commuting is also an excellent way to gain experience for riding in all weather conditions because you normally can’t wait for the weather to improve, you have to ride regardless. Such experiences will be very valuable during a bikepacking race.

My training methods are certainly not optimized aside from allowing me to enjoy my riding as much as possible and it fitting in well around my lifestyle. Some people preparing for a bikepacking race find that a more structured regime works better for them, so you should try different approaches and see what works best.

If you want a structured training regime then hiring a cycling coach is an option. Most cycling coaches will be able to put together a reasonably appropriate plan that is suited to your abilities and goals, but one coach who has a lot of experience competing in and coaching people for bikepacking races is Billy Rice who runs Invictus Cycling.

Having a coach can not only help you by giving you a structured training plan designed specifically for you, but also some people stay much more focused if they have an external person watching whether they are keeping up with the training goals that they’ve set. Personally, my internal motivation is strong, I wouldn’t want to have a rigid training plan, and I’m satisfied with my current fitness, so having a coach wouldn’t suit me, but other people are in a different situation.

Evans Cycles posted an interview with the coach of James Hayden, who won the 2017 Transcontinental Race. People simply aiming to finish the TCR sometimes also use coaches and rigid training plans, read about Bruno de Naeyer’s experience of Having a training scheme vs. following one.

A: Some people like to have structure and possibly even have someone keeping track of their progress, some people prefer to be more relaxed about their riding. Try both styles and see what works best for you.

Q: Will multi-day training rides help me to prepare for a bikepacking race?

This topic is discussed in more detail on the next page: Multi-Day Training Rides for Bikepacking Races.

It’s natural to assume that to ride the distances that are needed in ultra-distance bike races, you must do many, very long rides to get your body physically prepared. However, most coaches and trainers of ultracyclists believe that your body gains muscle and strength and becomes efficient at supplying your muscles with energy by riding, but rides of longer than about 4-6 hours don’t yield any additional gains in this respect. In fact, very long rides normally take longer for your body to recover from, which can prevent you from doing other productive training rides for a few days, so doing extra-long rides may even reduce the effectiveness of your physical training.

Even so, full-day and multi-day training rides are an essential part of your preparation for ultra-distance events because those rides should reveal any physical problems or pains that develop and help you to obtain the mental skills and experience needed to complete an ultra-distance race, especially one that is self-supported and so requires extra skills to be mastered.

If you experience specific pains during training, hopefully you can make changes to your position or equipment to improve Rider Comfort and prevent such problems from occurring during the race. In addition, such long rides provide the only true test of your Bike & Bike Components and Bike Accessories, so it’s essential to do such rides using as close to your final setup as possible and with plenty of time to allow you to make necessary changes before a big event.

Some very experienced bikepackers can therefore be completely prepared for a big event without doing any extra-long training rides, but less-experienced people should plan to do at least one multi-day ride during their training that simulates race conditions as much as possible.

A: Multi-Day Training Rides are far more important for developing mental skills and testing your equipment than they are for working on your physical capabilities.

Q: Is a power meter useful for ultra-distance cycling?

Power meters can be a useful tool to implement a more rigid training plan and to track the progress of your fitness during training. Other measures of your cycling fitness are readily available, like overall average speed, your performance in group rides, relative standings on Strava timed segments, heart rate at a given speed, etc. However, all of these are affected by many variables in addition to the power you put into the pedals, and so the noise in the data often overshadows improvements that you’ve made. A power meter is a far more precise measure.

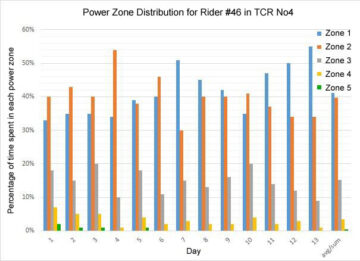

Although I find it interesting to have a power meter during training (although certainly not essential), I find it to be far less useful during a race when I just rely on feel to judge my level of exertion, which is something that several other power meter users have also said. However, it is still interesting to analyze the power data from the race afterwards, which is something that James Hayden has done on his blog and Jürgen Knupe shared this graph showing the time he spent in each power zone during the TCR in 2016.

Even though very little time is spent near the upper end of the power range during the race to avoid fatigue, that is not necessarily how you should spend your time when training. If you can train to be able to sustain a higher level of power then the power corresponding to the lower zones will be increased, making it feel easier to sustain a certain speed or riding slightly faster for the same perceived exertion.

I didn’t expect cyclists in professional road races to share much in common with TCR riders in terms of power data habits, but by watching this GCN video I discovered that many of them do the same as most TCR riders who have power meters, which is to mostly ignore the power data during the race and to only pay attention to it during training. Several also report that it’s useful to have power data recorded during the race to do some post-ride analysis, which is the main reason why I like to collect it during an event.

A: Power meters are useful tools that give pure performance measures that help with training. They are not so useful during a race.

Q: How much power do I need to sustain to complete a bikepacking race?

Part of the What Determines Cycling Speed? section covers the Effects of Increasing Power. The main finding is that power needs to be increased by a far larger percentage than the corresponding increase in average speed. For example, to increase the average speed from about 23 to 26 km/h, which is 14% faster, then a 28% increase in average power is needed.

If you want to know what level of power is needed to complete the TCR then the average-strength rider used in the simulations has an average power of about 130 watts (about 2 watts per kg), which I believe is quite typical, and such a rider who is on the bike for 12 hours per day is predicted to finish a typical TCR route around the time of the finish party. The stronger rider in those simulations has an average power of 165 watts (about 2.5 watts per kg), which not many people will be able to sustain throughout the race, and would finish almost 2 days sooner than the average-strength rider if also riding for 12 hours per day. If that same strong rider could maintain that power for 18 hours per day on the bike then they would finish in under 9 days and be competing for the victory.

Some people choose to sleep and rest more than others during the race but ride harder when they are on the bike. Other people take it easier on the bike, but spend less time off of the bike. Obviously, being able to do both would be ideal, but a trade-off normally has to be made. For most people, pedaling relatively easily for more hours is the more efficient and preferred strategy to maximize the distance ridden per day in ultra-endurance events, compared to pedaling harder for fewer hours per day. However, this is largely a matter of personal preference, so you need to find out what works best for you during training.

A: Averaging about 2 watts per kg for 12 hours of riding per day will allow you to finish most bikepacking races in a reasonable time. However, this is merely a VERY rough guideline – there are a LOT of other variables to consider.

Q: Should I be doing any other training aside from cycling?

Doing other forms of physical activities to get ready for a bikepacking race can help to improve muscles that are not stressed under normal cycling conditions but which may be stressed when on the bike for much longer lengths of time. The muscles most commonly focused on for this purpose are the core muscles, exercises for which are covered in an article at BikeRadar and in the GCN video below.

Personally, I find it mentally impossible to do any exercise in which I don’t move anywhere, so the only cross-training that I do is some hiking and occasionally cross-country skiing, which both help to develop core muscles. However, I don’t do enough and core strength is a weakness of mine (I failed to finish the 2015 TCR due to a pre-existing lower back problem, see my Race Report).

Other riders report doing gym sessions, swimming or climbing to improve their core and upper body strength to avoid problems when cycling ultra-long distances.

A: Improving core strength can help you to maintain a better position on the bike for longer and make you less likely to develop pains and injuries when cycling.

Q: How should I train during the final weeks before the race?

You obviously don’t want to be physically tired when starting a race, so for 1 or 2 weeks beforehand, it’s sensible to take it easier, don’t ride too hard and get plenty of rest. Even so, some people choose to ride from their home to the start of a race, which I did for the 2014 TCR. I rode about 600 km in 4 days then had a couple of days rest before the start. Because I was prepared to do 250-300 km per day during the race, doing 150 km days at an intentionally gentle pace and sleeping a lot in between felt very easy, seemed to take very little out of me, and I felt well-prepared on the start line.

The most important thing to do during the final few days is to get plenty of sleep and rest, because that will be in short supply once the race starts. Get all of your equipment ready and organized well beforehand so that you don’t have to stay up late in the final evenings/nights getting everything ready. Even if you think there are only a few last minutes things that you’ll need to do, get them done as early as possible because it’s amazing how many of those small things you will find that need to be done and how long each will take.

Many people arrive at the start with stories of getting minimal sleep in the previous nights due to sorting out their equipment, making last-minute adjustments to their routes, finishing up tasks at work, etc. You can be one step ahead of about half of the field if you arrive at the start line properly rested.

You should schedule time to prepare you bike for the race two or three weeks before the start. This may mean installing a new chain, rear tire, handlebar tape, brake pads, and anything else that has been wearing out during training. Doing this a few weeks before the race gives you enough time to do a couple of decent rides with the final setup to be sure that there are no problems with anything that you changed. This topic is covered in more detail on the Preparing Your Bike for a Bikepacking Race page.

A: As long as you don’t do anything too strenuous in the week or so before the race, then you should be fine. Make sure that you get lots of sleep during the final few days and get your bike prepared well beforehand.

General Tips

Apidura has a good article about training for ultra-distance events, including comments for several race winners. GCN have also made a video with Mark Beaumont that includes a lot of useful tips about physical and mental preparation and approach:

The GCN crew also made a video about training for a single-day ultra-distance event:

Last significant page update: February, 2018

This page is in the Physical Training section. The next page in this section is: